Civilians in Conflict (Data)

In the 2nd post of our methods series, we continue to explore the role of civilians in conflict data, focusing on the insights provided by UCDP and ACLED datasets. By examining variables such as “civilian targeting”, “deaths_civilians” and the event type of “violence against civilians”, we delve into the complexities of how to responsibly interpret and apply such variables when analysing the impact of conflict on civilians.

In our first post of ACCORD’s methodological blog series on How to best describe a conflict in the context of COI, we examined ACLED’s "Conflict Exposure" measure in detail. In the current post, we will continue our exploration of the role of civilians in conflict data. Specifically, we will continue to assess what quantitative conflict data collections can tell us about how civilians are involved and affected, based on commonly used variables indicating the number of deaths, types of events, actors involved, but also more distinctive variables indicating characteristics of incidents, such as so-called “civilian targeting”, which was added as a new variable to ACLED’s datasets in 2023. As the impact of security-related incidents on civilians is a central aspect of many COI products dealing with security situations, this blog post will introduce various variables that focus on civilians and discuss their different meanings and possible implications. In this blog post, our focus lies on the datasets provided by UCDP, the Uppsala Conflict Data Program, and by ACLED, the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project, two of the most widely used conflict data providers in the field of COI.

Different datasets, different variables, different insights:

No matter what conflict dataset you are working with, whether it is ACLED or UCDP’s Georeferenced Event Dataset (GED) or any other, it is important to be aware that data collection methodologies vary and thus lead to different outcomes. ACLED and UCDP, for instance, seemingly measure the same, i.e. conflict-related incidents, yet their figures on incidents and casualties consistently differ (Raleigh et al., 2023; Eck, 2012). Data collection practices, resulting datasets and their reliability and validity are significantly shaped by various decisions made by their creators (including decisions regarding conceptual, coding, and sourcing variations) (Raleigh et al., 2023, pp. 1-3). (More general information on how to deal with quantitative data in the context of COI research can be found in chapter 5 of ACCORD’s Researching Country of Origin Information Manual.)

Tip: Consulting the manuals of the datasets, known as codebooks, is highly beneficial. These codebooks offer valuable guidance and detailed descriptions of the data collection methodology, variables, and more! If you want to have a look into examples of such codebooks, check the ACLED and UCDP GED Codebook.

Looking specifically at the variables that address the role of civilians in conflicts, we also see that ACLED and UCDP collect different types of information. This becomes apparent for example when taking a look at UCDP’s GED, where civilian death tolls are displayed separately in the variable named “deaths_civilians”. This variable represents “the best estimate of dead civilians” per conflict incident (UCDP, 19 March 2024, pp.10-11). In general, UCDP distinguishes in its dataset between three different categories of violence: non-state, state-based and one-sided violence (UCDP, 19 March 2024, p. 6). Civilian deaths in events categorised as “non-state violence” or “state-based violence” are, according to the codebook, so-called “collateral killings”, namely civilian deaths as a result of fighting by two warring parties. This includes cases of “civilian bystanders receiving fatal injuries” or when civilian fatalities are caused, for example, by imprecise air strikes that did not originally target civilians (UCDP, 19 March 2024, p. 24). In the case of the third category, one-sided violence, the variable “deaths_civilians” refers to the number of civilians killed by the “perpetrating party” (UCDP, 19 March 2024, p. 7-11). However, only “the use of armed force by the government of a state or by a formally organized group against civilians which results in at least 25 deaths” is considered as one-sided violence, extrajudicial killings in custody are explicitly excluded (UCDP, 19 March 2024, p. 30).

In comparison, ACLED does not specifically itemise civilian deaths in its datasets, as ACLED provides only one variable in regard to fatalities, which encompasses all deaths caused by an event. On the basis of this variable alone, it is not possible to draw conclusions about the impact of an event on the lives of civilians. It is therefore necessary to make use of other variables provided by ACLED, namely the Actor columns, the coded event type, and the relatively new variable “civilian targeting”:

- Civilians as actors in ACLED data: ACLED defines civilians as victims of violent acts and as being unarmed and unable to exert political violence (ACLED, 7 October 2024, p. 18; 30). This definition entails that ACLED only codes civilians as actor within one of its four actor variables, “actor1”, “associated actor1”, “actor2”, “associated actor2”, for event types that fall into the categories of protests, riots or strategic developments; or as “actor2” or “associated actor2” only for event types that fall into the categories of “explosions/remote violence” or “violence against civilians”. Civilians are not recorded as actors in events that are coded as “battles”.

- Violence against civilians as an event type: “Violence against civilians” is coded as an event type in cases of “violent events where an organized armed group inflicts violence upon unarmed non-combatants”. This type of violence is defined as one-sided, since it is assumed that the perpetrator is the only actor able to use force. Accordingly, “violence against civilians” is coded when an unarmed person or a person who is unable to defend themselves or carry out a counterattack is killed or injured. On this basis, ACLED explicitly includes “extrajudicial killings of detained combatants or unarmed prisoners of war” in this event type category. In its codebook, ACLED specifies that events are only coded as “violence against civilians” if they do not occur “concurrently with other forms of violence […] coded higher in the ACLED event type hierarchy”, such as riots (ACLED, 7 October 2024, p. 18).

- Civilian targeting as a characteristic of various event types: ACLED’s “civilian targeting” variable is coded when civilians are recorded as being “the main or only target of an event”. Events in which civilians were the main or only target include not only those coded as “violence against civilians”, but also those coded as “explosions/remote violence”, “riots” and the sub-event type “excessive use of force against demonstrators”. The code “civilian targeting” is not assigned for events in which civilians were unintentionally harmed (ACLED, 7 October 2024, p. 23).

Practical implications:

From the variables and their descriptions above, various kinds of insights about civilians in conflict can be derived:

1. The use of “civilians” as actor allows to determine the number of security-related incidents in which civilians were coded as “actor1”, “associated actor1”, “actor2”, “associated actor2” in a given period. However, as ACLED does not code civilians as “actors” in events categorized as “battles”, even though they may be injured or killed in such incidents, this figure does not represent the number of all events that affected civilian lives.

2. The event type “violence against civilians” shows the number of security-related incidents in a given period in which unarmed civilians were the victims of violence in the form of sexual violence, attacks, or abductions/forced disappearances. Since this “event type” is however limited to these three “sub-event types”, this figure does not represent the number of all events in which civilians were subjected to violence.

3. The variable “civilian targeting” allows us to determine the number of security-related incidents within a given time frame in which civilians were the main or only target, but this figure does not represent the number of all incidents in which civilians were affected.

Options 2 and 3 differ in that incidents coded as “civilian targeting” include not only “violence against civilians” events but also other event types. However, all incidents coded as “violence against civilians” are always also coded as “civilian targeting”.

By exploring the data in these different ways, you have the option of analysing which types of events are featured as security-related events when looking at either option 1 or 3 and, for example, how many fatalities resulted from these incidents; thereby always bearing in mind that these are not exclusively civilian fatalities!

Note: As stated in ACLED’s codebook, the information on fatality figures is usually the “most biased” and “least accurate” part of reporting on conflicts. Both armed groups and media outlets can manipulate these figures to serve political agendas. Consequently, these figures should be regarded as a “indicative estimate” rather than “definitive fatality counts”. (ACLED, 7 October 2024, p. 38)

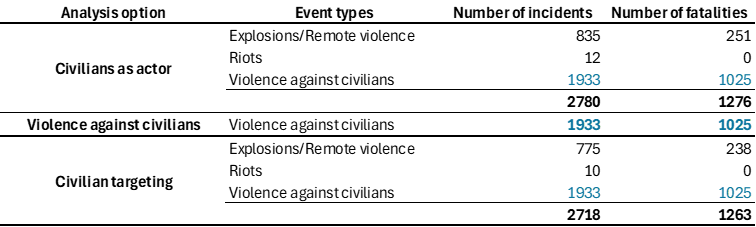

To better illustrate this breakdown and how the analysis options affect the figures output, the table below provides a comparison:

ACLED Data: Iraq, 2020-2024, filtered for “disorder type”: “political violence” (including the following event types: battles; explosions/remote violence, riots and violence against civilians)

Figure 1. Table based on ACLED: Curated Data File, Middle East (28 February 2025), as of 5 March 2025.

As we have now seen, the ACLED data provide different indicators for analysing the impact of conflicts on civilians, each of which captures – to some extent – different aspects. This differentiation is further highlighted in cases where ACLED has defined specific practices for coding civilian deaths that occur indirectly without direct targeting, i.e. without the incident being coded as "civilian targeting". According to ACLED, this was particularly relevant in Iraq. ACLED notes that civilian deaths caused by indirect fire during battles are counted in the total number of deaths, but civilians are not coded in the actor variable. In the case of remote violence, civilians may be listed as associated actors when one armed group targets another. These deaths or injuries are then recorded in the “Notes” column and again reflected in the number of fatalities (ACLED, 29 November 2023).

The example above also illustrates why it would not be useful to focus solely on the variable of “civilian targeting” when producing COI products on the security situation in a given country. Doing so would not adequately reflect the reality of the civilian population in the respective country. Civilians are affected by conflict not only when they are directly targeted in security-related incidents, nor when civilians are killed in such incidents (as estimated, for example, in the UCDP GED data). This brings us back to the new ACLED measure of conflict exposure introduced in our last blog post: While the number of incidents in which civilians were directly targeted and the number of fatalities can be used to describe the scale and intensity of a conflict, ACLED’s conflict exposure measure additionally illustrates the impact of a conflict on civilians, as indicated by the estimated number of people exposed to it. In this regard, ACLED defines exposure to conflict broadly, specifying that individuals can be adversely affected by exposure to conflict in various ways.

Recommendations:

In conclusion, we recommend:

- To be aware of the different meaning and implications of using various indicators regarding the role of civilians in conflict in your respective dataset.

- To use both the variables of “civilian targeting” and “conflict exposure” when preparing quantitative data analysis for your COI products

- It is more insightful to compare analysis results over similar time periods, as this approach highlights trends rather than reporting precise figures (which are not provided by either ACLED or UCDP, as both are based on estimates dependent on their methodologies).

- And, as always, assessments of the security situation should not be based solely on quantitative analysis of event data.

Sources:

ACLED – Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project: How does ACLED code the indirect killing of civilians?, last updated: 29 November 2023

https://acleddata.com/knowledge-base/indirect-killing-of-civilians/

ACLED – Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project: Codebook, 7 October 2024

https://acleddata.com/acleddatanew/wp-content/uploads/dlm_uploads/2024/10/ACLED-Codebook-2024-7-Oct.-2024.pdf

ACLED – Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project: Curated Data Files, Middle East (28 February 2025), as of 5 March 2025

https://acleddata.com/curated-data-files/#MiddleEast_2015-2025_Mar5

Eck, Kristine: In data we trust? A comparison of UCDP GED and ACLED conflict events datasets. In: Cooperation and Conflict, Volume 47(1), 2012, pp. 124-141 https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/0010836711434463

Raleigh, Clionadh et al.: Political instability patterns are obscured by conflict dataset scope conditions, sources, and coding choices. In: Humanities & Social Sciences Communications, No. 74, 2023

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41599-023-01559-4.pdf

UCDP – Uppsala Conflict Data Program: UCDP Georeferenced Event Dataset Codebook, Version 24.1, 19 March 2024

https://ucdp.uu.se/downloads/ged/ged241.pdf