Menace, Negotiation, Attack: The Taleban take more District Centres across Afghanistan

Original link (please quote from the original source directly):

https://www.afghanistan-analysts.org/en/reports/war-and-peace/menace-negotiation-attack-the-taleban-take-more-district-centres-across-afghanistan/

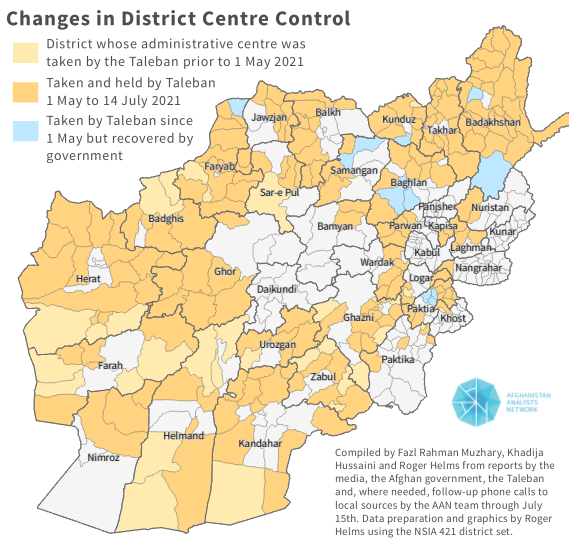

The Afghan government has continued to lose district centres to the Taleban. By our reckoning, the insurgents have gained control of almost 200 district centres since 1 May, most of them since mid-June. Added to the ones they already controlled, that puts the insurgents in charge of just over half of all Afghanistan’s district centres. In a detailed new map published today, the Taleban’s apparent strategy becomes clearer: an initial push in the north, where resistance to their rule in the late 1990s/early 2000s was strongest, a focus on border crossings and other lucrative locations, and an avoidance so far of provincial capitals and of eastern areas which border Pakistan. In this report, Kate Clark and the AAN team try to make sense of the patterns of districts falling or standing, with contributions from Ali Yawar Adili, Ali Mohammad Sabawoon, Fazal Muzhary, Roger Helms, Khadija Hussaini, Obaid Ali, Rohullah Sorush, Roxanna Shapour, Sayed Asadullah Sadat and Thomas Ruttig. All maps and charts in this report are by Roger Helms.

Afghanistan’s district centres have continued to fall to the Taleban, as can be seen by comparing Map 1, above, showing the situation on 14 July (detailed PDF version also available here) and Map 2, below, showing the situation on 29 June (below). Only four provinces have district centres still entirely in government hands: Kabul, Panjshir, Kunar and Daikundi. Regions still largely under government control are much fewer than they were: the east, almost all of the Hazarajat and much of the area around Kabul, including much of Logar, eastwards to Nangrahar, and north through most of Kapisa, Panjshir and into central Baghlan. Khost and most of Paktika look more robust on the map than they are: the appearance of government-held districts masks what is actually more an archipelago of control as in many districts, only the district centres are still with the government. By our reckoning, the Taleban have captured and held 197 district centres since 1 May, which when added to those they already held, means they hold 229 district centres a little over half of all the country’s district centres. The government lost, but have then recaptured 10 districts. Some districts are still volatile, but we have tried to be as accurate and up-to-date as possible.

As always, there is debate about what ‘control’ means: governing, the ability to travel safely, or deny the other side movement? This report measures only who controls the district centre, a metric chosen for its simplicity and relative ease of determination. This means that a district may be classed as having fallen to the Taleban even if there are still Afghan National Security Forces (ANSF) present outside the district centre. In other districts, the ANSF and government officials have withdrawn from the district centre and the Taleban have not yet established defensive positions, nor are they governing. Nevertheless, we have also classed those as under Taleban control.

It is also true that many of the districts whose centres have fallen were already under de facto Taleban control, with ANSF and officials isolated in the district centre. The decision to capture these district centres is what has marked this phase of the war so vividly, and therefore, our metric is relevant, as well as simple. The Taleban could have tried to capture them en masse before, but, it seems, chose not to. Their apparent change of strategy coincided with 1 May, the date stipulated in the United States-Taleban agreement signed in Doha on 29 February 2020 when all international forces should have withdrawn. 1 May is the date, therefore, when we began logging changes in district control. The Taleban surge also followed US President Joe Biden’s decision, announced on 14 April 2021, to pull American forces out completely, rapidly and unconditionally. The effects of this decision, following the US’s attempts at a peace process, which had bolstered Taleban morale and fighting ability and demoralised the ANSF, were discussed in our 2 July report.

Any suggestion that the Taleban’s capture of districts might have peaked, that the mass fall of centres to the group was the result of it targeting ‘low-hanging fruit’ – district centres where ANSF and officials were already surrounded by Taleban forces – proved to be a mistake. District centres have continued to fall, as the chart below shows.

In this report, we take a country-wide look at the conflict. We hope to follow this up with in-depth reports of particular regions, provinces and districts in the coming weeks.

What has changed in the last two weeks

Our earlier report, published on 2 July, focused on the Taleban’s onslaught on northern Afghanistan, which appeared to be a pre-emptive strike aimed at forestalling any resurrection of a Northern Alliance that could mobilise defences against the Taleban. Since then, one of the two northern provinces, then still relatively untouched, Badakhshan, has largely fallen to the Taleban. Only the provincial capital, Faizabad, and its district and the neighbouring Yaftal-e Sufla are in government hands; the latter was lost and recaptured. The Taleban now also control the border crossing into Tajikistan in Eshkashem district.

Badakhshan was the one province that the Taleban never gained any part of during their rule in the late 1990s/early 2000s, protected as it was from advancing Taleban forces by Panjshir to the south and Northern Alliance frontlines to the west. While the Taleban did move closer in the years after they captured Kunduz in 1997, they were never able to move beyond part-way through neighbouring Takhar. The Taleban have now captured even those districts where there had been little or no recent Taleban presence, such as Shughnan and Wakhan. Many soldiers in Badakhshan were reported to have surrendered and 2,400 to have fled north across the border into Tajikistan. The takeover by the Taleban of provinces bordering Tajikistan prompted Tajik president Emomali Rakhmon to order 20,000 troops to the country’s border with Afghanistan.

The Taleban had already captured most district centres in Kunduz and Takhar at the time of our last report. Now the provincial capitals, Kunduz and Taloqan, are under threat. Local journalists speaking to AAN on 15 July, said that in both cities, people were trying to cope with rising food prices. The prices of electronic goods, clothes, carpets, furniture and property prices had all plummeted, journalists said, while food prices had risen: the price of five kilos of cooking oil, for example, which had been selling for eight dollars (600 afs) was now 11 dollars.

Abdul Basir, a shopkeeper from Taloqan, also speaking on 15 July, said the nearest Taleban checkpoint was now located only a few kilometres from the provincial governor’s office. He said that many people had fled due to fighting around the city. People were only buying food. No one was coming to his shop to buy Eid clothes. Indeed, he said, there was no sign of Eid shopping or other preparations in Taloqan at all. He had just been to the funeral of a close friend, one of 12 members of a Popular Uprising Force who had been shot dead at a security checkpoint the previous night.

Much of Herat province is also now in Taleban hands, including Afghanistan’s main border crossing into Iran, Islam Qala, captured on 8 July after soldiers fled across the border. Overnight, on 13/14 July, the Taleban also moved into the district centre of Spin Boldak in Kandahar province on the border with Pakistan after heavy fighting. It appears that the ANSF withdrew to a base inside the Wesh bazaar, while the Taleban took control of the district centre. With the capture of Islam Qala and Spin Boldak, the Taleban now hold two of Afghanistan’s three most important border crossings. Map 3 below shows Afghanistan’s border crossings and main roads against the backdrop of district centre control.

Such crossings appear to have been one focus of the Taleban offensive: the Sheikh Abu Nasr Farahi dry port in Shibkoh district of Farah province on the border with Iran was reported to have fallen on 8 July, Torghundi in Herat on the Turkmen border on 9 July and earlier, in the fourth week of June, Sher Khan Bandar in Kunduz, Hairatan in Balkh and Aqina in Faryab – these border Tajikistan, Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan respectively. Hairatan was recaptured by the ANSF in a counteroffensive on 29 June.

In Paktia, Jaji Aryub’s district centre on the border with the Kurram Agency, one of Pakistan’s Federally-Administered Tribal Area, was ceded to the Taleban. In a report published in April on the disbanding of the ALP, AAN interviews with ANSF and other locals in Jaji Aryub had suggested the government’s hold there was strong it reportedly fell after the government failed to get reinforcements through. Jaji Aryub is also the site of the Paiwar Pass, location of a major battle in the second Anglo-Afghan war when the defeat of the British changed the balance of power in Kabul.

Controlling such border crossings allows the Taleban to tax traders and, in turn, weakens the government, given how much it relies on customs duties. The scale of the revenue loss is vast. In the first five months of 2021, according to acting Minister of Finance Khaled Payenda, the government collected 35 billion afghanis – more than 438 million USD in customs; the equivalent of 330 million afghanis, or about four million dollars a day. [1] Customs are of fundamental importance to the government, a revenue stream that keeps state and services running. It has now lost much of that revenue.

The Taleban have also gained control of new sections of the ring road that circles Afghanistan from Mazar-e Sharif in the north to Herat in the west, Kandahar in the south and Kabul in the centre. Again, the gains are two-fold: roads are places to tax/extort money from travellers and to look for off-duty soldiers, government officials and the like, while controlling a road also denies or at least weakens government officials and ANSF freedom of movement. Kabul is still linked to the border to the east, via Nangrahar and the Torkham border crossing into Pakistan, but the road is not without problems, especially at choke points like Sarobi. The government also holds the district centres through which the ring road north of Salang to Mazar-e Sharif passes; although Khenjan and Doshi districts of Baghlan and Hazrat Sultan of Samangan were lost, they were recaptured by the ANSF. However, the Taleban have checkposts on the highway on stretches of the road beween Doshi and Pul-e Khumri, Pul-e Khomri to Samangan and Samangan to Mazar.

In the southern reaches of the ring road, the Taleban now control all the district centres along the road from Qalat in Zabul province to Herat, except Tarnak wa Jaldak in Zabul, and Daman, Kandahar city and its district, and Zheray in Kandahar province.

What does the government still hold?

What remains in government hands is as important as what has fallen. Noticeable is that not one of the provincial capitals has fallen, although many look vulnerable: Qalat in Zabul, Sar-e Pul city, Maimana in Faryab, Lashkargah in Helmand, Taloqan in Takhar and even Pul-e Khumri, Faizabad and Kunduz city. There has been speculation that the Taleban are waiting for the final departure of the last international troops to try to take the cities; sparing them may have been specified in a supposed secret annex to the US-Taleban February 2020 agreement. However, there have been attacks on some suburbs, for example, Kandahar and Kunduz. Local journalists speaking to AAN on 15 July said areas of Kunduz city had already been handed over to the Taleban, who, unlike the ANSF in the province, are well-supplied; one journalist said their fighters could fight for two more months without running out of supplies and food.

The Hazarajat

Hazarajat is still an island of government control, but one attacked by Taleban from all sides on what amounts to the long ‘ethno-border’ between mainly Hazara and mainly Pashtun (or Tajik in the north) districts, and with roads to the outside increasingly controlled by Taleban.

Discussing ethnic and sectarian issues is always sensitive in Afghanistan, but in this instance, it has to be raised. The Taleban argue that they are an all-Afghan group, most recently in a statement on 23 June. It is a movement “formed,” the statement said “from the diverse ethnic groups, tribes and regions of the country and is a representative force of all people, ethnicities and strata” and “therefore reassures all citizens that none will be treated in a discriminatory, vindictive, condescending or hostile manner” and again, later in the same statement that it wants to “reassure women, men, minorities, media and all strata that the Islamic Emirate shall hold them in high esteem.” Yet the Taleban are a faction of Sunni Muslims, mainly mullahs and madrassa students. Also, athough there are more Tajik, Uzbek, Aimaq and Sunni Hazara fighters, commanders and officials in Taleban ranks than there were in the 1990s/early 2000s – a reflection of their long-term strategy to co-opt at least the clerics of non-Pashtun populations (see our 2011 paper here) – it is still a movement dominated by Pashtuns, especially southern Pashtuns, and especially at the national leadership level.

When the Taleban governed most of Afghanistan in the late 1990s/early 2000s, there was a tiny sprinkling of Shia officials (for example Sufi Gardezi, district governor of Yakawlang). The movement also co-opted some Hazara leaders, notably Ustad Akbari in Shahrestan district (now in Daikundi), who told this author in 1999 that he had taken this course of action because he did not want the war fought over Hazara lands. However, both pre-2001 and during the insurgency, Afghanistan’s Shia Muslims are de facto excluded from its ranks, because it is a Sunni Muslim clerical faction. [2]

Added to this political exclusion, there is also a history of violence. During their rule, the Taleban carried out reprisal massacres of civilians and burnt earth operations against various non-Pashtun communities (see our 2 July report for details), but Shia Hazaras and Sayeds living among them were most often targeted.

Some members of other ethnic groups have argued against what they see as ‘Hazara exceptionalism’, saying that the prospects for any Afghan living under Taleban rule are not good. Some pro-government Pashtuns, for example, have expressed a fear that because they are also Hanafi Sunnis, the Taleban would view them even more badly than the Shia Hazaras – as traitors. Nevertheless, the historical precedent indicates that prospects would be particularly bad for Hazaras. The other group who can only expect political exclusion in any area of ruled by the Taleban are, of course, Afghanistan’s women.

An ‘island’ cut off

All of the three major roads connecting Bamyan city and the Hazarajat with the north or with Kabul now pass through Taleban-controlled areas, as the Taleban have captured districts on the borders of or just outside Hazarajat. The mixed district of Jalrez [3] in Maidan Wardak province was captured by the Taleban in June; with that the movement came to control the shortest and most direct of Bamyan’s routes to the capital via Maidan Wardak.

In the last week, the Taleban have also captured the centres of various districts with majority Tajik or Sunni Hazara populations on the north-eastern edge of the Hazarajat; these had been securely held by the group in the late 1990s/early 2000s. They include those through which the second main road out of Bamyan city, which goes to the east, passes. It intersects with the ring road going north/south – to the Salang Tunnel and northern Afghanistan or to the Shomali Plains and Kabul. The government still holds the first district east of Bamyan, Shibar, but the Taleban have positions on the Shibar Pass which the road goes through. Beyond that, the Taleban captured the next district along, Sheikh Ali in Parwan province on 12 July and beyond it, Ghorband, also in Parwan province, on 25 June.

The third road from Bamyan goes north and is also now problematic for the government. It passes through Shibar and then skirts two districts whose centres have fallen to the Taleban, Kahmard on 12 July and Saighan on 13 July, both in Bamyan province. Beyond them, the road passes through Tala wa Barfak in Baghlan province; its district centre fell to the Taleban in June.

Bamyan had also already lost its alternative partly paved route north, from Yakowlang district to Mazar via the two Dara-ye Suf districts, which were captured in June. This was an important route for refugees fleeing Taleban attacks and reprisals against civilians when the movement finally captured Bamyan in 1998, and also for the Northern Alliance in those years as it linked to strongholds further north. [4]

On the western edge of Hazarajat, much of the road west to Herat from Ghor’s Lal wa Sar Jangal, a district the author once described as the “sane heartland of Afghanistan,” is now Taleban-controlled. In southern Hazarajat, the Taleban have been attacking the Hazara-majority district of Pato in Daikundi province since 10 June. Etilaat-e Roz newspaper reported on 18 June, for example, that hundreds of families had fled heavy fighting in the Sartagab area, “leaving only the elderly and disabled” behind. It reported that “several heavy Taliban attacks were repulsed by popular mobilization forces,” but that the area had at last fallen and that after that, the Taleban had “set fire to residential houses and crops, including wheat fields.” By 7 July, with the fighting continuing, the numbers of displaced families had risen to the thousands (see this media report). Pato district centre remains in government hands.

The three Hazara-majority districts of Ghazni province have also come under attack. Nawur came under an onslaught from Taleban fighters from neighbouring Ajristan district – they captured a security post in the Qoshonk area on 4 July – and also from the Shaghna Pass, which borders both Jaghato districts of Maidan Wardak and Ghazni, and up to the Hesarak area, close to the district centre, on 6 July. They were pushed back after reinforcements arrived from Malestan and Jaghori districts on 7 July. However, the situation is still volatile. The Taleban attacked the district centre again overnight on 14/15 July. The district governor told AAN that the Taleban fighters “reached to a distance of 200 metres from the district police compound. The Taleban fighters were telling the security forces to surrender and the security forces were telling them to come closer.” The fighting, he said, “lasted from 11 pm to 4 am, when the Taleban retreated.”

Malestan has also been under attack, again by fighters from Ajristan and also Khas Uruzgan district. Malestan district centre fell in the afternoon of 12 July, hours after government forces and district governor had withdrawn to neighbouring Jaghori and after government forces – the Afghan National Army (ANA) Territorial Force, which is a locally-drawn force, police and Uprisers – who were defending the district centre had warned it would fall unless they received supplies. Jaghori district, meanwhile, has also been under Taleban attacks since 4 July, with fighters trying to advance several times from neighbouring Qarabagh, Muqur and Gilan districts. Now that Malestan has fallen, Jaghori is also very much under pressure. [5]

The East

It is noticeable that most of the east and Loya Paktia (Khost, Paktia and Paktika) is still in government hands: possibly, the Taleban’s sponsors, the Pakistani ISI, do not want fighting on this stretch of Pakistan’s borders just yet. At the same time, there is also government strength, although more so in the east than the southeast. In Nangrahar and Kunar where the Taleban have attacked government positions, they have achieved little. So far, the ANSF, along with Uprising Forces, have defended their positions successfully.

Nangrahar’s fight against the Islamic State in Khorasan Province left it with a proficient ANA and a network of strong, pro-government militias, and a relatively weak Taleban – all of which may make it difficult for the Taleban to expand there. Khalid Gharanai, who co-authored a recent report for AAN on the ISKP in Kunar, reported that in May the Taleban did launch attacks on two of Nangrahar’s southern districts which border Pakistan, Deh Bala and Pachir wa Agam districts. Although they were able to run over some security bases and outposts, he said they were stopped by Uprising Forces supported by the ANSF. More recently, he said, the Taleban have been focusing operations on other southern districts: Khugyani, Sherzad, Nazian and the one district in the province whose centre has been captured by the Taleban, Hesarak (on 5 July); it borders Taleban-held Azra in Logar provinces.

Kunar is in a similar position to Nangrahar in terms of relative Taleban weakness and the relative strength of the ANSF and Uprising Forces. Less than two weeks ago, the Taleban launched attacks on Ghaziabad, Bar Kunar and Marawara districts, all in the province’s northeast, but the ANSF were able to defend them. The Taleban only made slight progress, capturing Marawara district’s Ghakhi Pass, an unofficial border crossing point to Pakistan, which has been closed to traffic for almost two decades, and some villages in Ghaziabad. Since then, reports Gharanai, the Taleban have massed up to a thousand fighters in Kunar ready to launch an offensive, but have yet to receive a final order from their leadership. The perception locally, he said, is that for the time being, they may leave Kunar the way it is, because they want to move some of their leaders to mountainous areas in the province without attracting ANSF attention, or provoking counter attacks by the Afghan airforce or other forces.

Loya Paktia

In the south-east, Khost’s district centres are all in government hands except Qalandar, which was held by the Taleban before 1 May, and Musakhel, which fell on 13 July. Government strength in Khost is largely down to the Khost Protection Force (KPF), a militia that was controlled by the CIA, but which has reportedly been handed over to the NDS; it has a record of committing serious abuses, including summary executions and torture (see AAN reports here, here and here), but also of staunchly fighting the Taleban. The KPF grew out of the 25th army division, reconstituted after 2001 with former PDPA, especially Khalqi military men. It was saved from being disarmed and demobilised in the early years of the Karzai administration by its close links to the CIA. One former mujahed commander recalls that they had problems in the same locations with the parents of some of today’s KPF commanders (unusually, the mother of one KPF commander held a post with her husband in the 1980s). The KPF has developed since its early years, recruiting from local tribes, including Dzadrans who are anti-the Haqqani network.

The situation in Paktia is less positive for the government. In the last two weeks of June, it lost a swathe of its northeastern districts, including the two bordering Pakistan, and Zurmat and Rohani Baba in the southwest bordering Logar and Paktika. In Paktia as well, it is the KPF which holds the three Dzadran districts still with the government, Shwak, Zadran and Gerda Tserai. The government also still holds Gardez city and district. The KPF was also involved in the government’s recapture of Ahmadabad (with Ghani’s own Ahmadzais) and Sayed Karam districts.

The loss of Zurmat district, which lies just to the southwest of Paktia’s provincial capital, Gardez, on 2 July, may prove critical as it lies on the supply route to Paktika and the region’s most important ANA garrison. Paktia is critical to the government holding both Khost and Paktika because of supply lines. In a forthcoming piece focussing on Zurmat, we will argue that the Taleban strategy appears to be just this: attack Paktia first to cut off and weaken Paktika and Khost.

If it can be said that the Taleban have tested the ANSF in Nangrahar and Kunar and not defeated them, in Loya Paktia, there has only been sporadic resistance from the ANSF, and from Uprisers mainly only in Zurmat, as well as some limited counteroffensives by the KPF. Elsewhere, the Taleban have had almost no need to test the ANSF. Where district centres have fallen, it was typically after a quick ANSF withdrawal, often after an agreement mediated by tribal elders. Taleban pressure applied through elders, mosques and even mothers (more on this in the forthcoming report) succeeded in many places, without there having to be much fighting at all.

The government’s decisions on where to focus its efforts on recapturing districts is also telling: a focus on protecting the road from Kabul to Mazar north of the Salang Tunnel, three districts in Paktia which help protect Khost and Logar, and Yaftal-e Sufla in Badakhshan, which neighbours provincial capital Faizabad.

Conclusion

The advance of the Taleban in recent weeks is undeniable and significant. Only two months ago, on 1 May, this author conjectured that if the Taleban did try for military victory, there was “every prospect that any Taleban drive to intensify the violence will be resisted, with immense suffering to countless Afghans.” I overestimated the ANSF’s capacity or desire to defend positions and territory – even though the evidence of the weakness of the ANSF and of the government was all there and I had written about aspects of it at length. Too many of those at the top have viewed the ANSF – and state positions in general – as opportunities to make money. Such corruption, which causes systemic weakness in military forces, is entrenched in the post-2001 political economy where the state was reliant on unearned foreign income – aid or military spending – known as ‘rent’ in academic circles, because it accrues without work or effort. In that same 1 May report, I wrote:

Scholars have described how breaking the relationship between work and reward encourages a ‘rentier mentality’ when those in power feel entitled to rewards without effort. In Afghanistan, one can trace how rent has helped shape a political class unused to making hard decisions (because the income always flows anyway), financially insulated from the population and organised to jockey for power and gain access to rent, rather than to do anything…. The question now is whether the Republic’s political class is capable of the change needed, as international troops withdraw and international support diminishes.

It turned out that the ill-prepared Republic was to encounter a very well-prepared Taleban very soon after that report was published: the time to make those changes had disappeared.

Another clear indication of the relative strength and weakness of the Republic and the Taleban on the ground, in retrospect, was the 2019 presidential election. The map below of the polling stations which opened on election day that used data collated by USIP’s Colin Cookman (first published here) shows vividly where the government was strong enough to organise an election in the face of Taleban opposition. There were huge swathes of the country where sites that were open in previous elections were closed, illustrating the Taleban’s growing strength on the ground. Except across the north, it maps out surprisingly well onto who controls district centres today.

The 2019 election was telling in other respects. Turnout was the lowest since 2001; fewer than one in five registered voters cast their ballots and turnout was low even where voters could safely get to the polls. There following an opaque complaints process and a disputed result. Both Ashraf Ghani and Dr Abdullah claimed victory and each held rival presidential inaugurations. Only US and international support enabled Ghani to conclusively take the laurel. At the time, we called the elections a “bad omen” for the then prospective peace talks between the Republic and Taleban: “If Ghani, Abdullah and others cannot agree on a united team, and a common negotiating position, they will only play further into the hands of the Taleban.” It has turned out that the elections were also a bad omen of how the Republic would fare in the war once its international military allies left.

The importance of morale

Across the country were many districts that could be characterised as ‘low-hanging fruit’, places where the government and ANSF controlled the district centre, often precariously so, and little else. Yet Taleban gains since 1 May have gone well beyond the capture of those centres. Even if the government had intended to let some districts fall to the Taleban to protect supply lines and concentrate resources on what it could defend, the damage to morale of the security forces and of the nation of seeing districts toppling like dominoes cannot be underestimated. [6]

In some places the Taleban have fought, but often a mix of menace and negotiation have been enough to get the ANSF and local officials to cede district centres. The Taleban’s narrative that it is heading to victory, in many cases seems to have proved more powerful than the government’s insistence that it is in control, represents national unity and can protect the people. Those in charge of district centres, especially if government forces were short of supplies – food or ammunition – were often left to decide whether they wanted to be the last standing district in a province or whether it was better to concede rather than fight on. There are also districts, of course, where the ANSF has fought on and been overrun, or has successfully defended positions. And there are districts that have been ‘flipped back’.

In Afghanistan’s four decades of war, morale has often proved more powerful than apparent military might, with the country ‘flipping’ when forces feared ending up on the losing side. Afghanistan is not at that point yet. So far, the tide has been with the Taleban, but they may also reach the stage where it is their forces that are overstretched. The ‘wild card’ of popular mobilisation, whether militias are organised by the state or not, may yet come into play, whether in defending towns and cities alongside the ANSF or in counteroffensives. It seems for now, however, that President Ashraf Ghani has backed away from government support to new militias, to the upset of some regional leaders and local communities keen to be given the resources to defend their areas (see reporting on 12 July by Tolonews). Where there is strong popular resistance, it has been less easy for the Taleban to win territory. In other places, the local population or local elders have often preferred a handover to the Taleban and an end to the fighting, over the presence of government forces which would remain a target, causing more fighting and destruction; this at least appears to have been the case in some of the districts falling in the south-east.

The Taleban have been fulsome in relaying how organised, fair and careful they are behaving in the districts which have fallen under their control. Snippets of accounts of life in newly-captured districts have, however, been mixed – government officials called into work, fearing to go, or continuing to work, women banned from working and allowed to only leave the house with a mahram (close male relative), government bureaucracy co-opted, and surrendered soldiers being sent home after giving guarantees or even money – or shot or taken prisoner. In some cases, Taleban district governors have moved into the offices of government’s governors. In some places, government documents were burnt. In places like Pato in Daikundi, there have been accounts of crops and houses burned in areas where there had been resistance.

While these accounts are difficult to verify, any reports of atrocities committed by the Taleban against the civilian population or captured members of the ANSF – whether authentic or not – could help shift the tide of the war, although whether they would provoke resistance or compliance is difficult to predict. At the same time, there have also been accounts of government forces abusing captured Taleban or those they suspect of sympathising with the movement. The impression already is of a war that has become far uglier in a matter of weeks.

The Taleban’s claim on 23 June to have restored “peace and security in many districts” is belied by one clear metric that is available – the number of new internally displaced persons (IDPs) in Afghanistan. On 13 July, the United Nations refugee agency, UNHCR, warned of a looming humanitarian crisis in Afghanistan after “an estimated 270,000 Afghans have been newly displaced inside the country since January 2021 – primarily due to insecurity and violence.” The numbers of those killed, injured or left permanently disabled – ANSF, Taleban and civilians – or of the newly widowed or orphaned are yet to be counted, if, indeed, they ever are. The losses to families because of crops untended and harvests ruined may also never be known. All that is clear is that the violence shows no sign of abating.

Edited by Martine van Bijlert and Roxanna Shapour

References

| ↑1 | Payenda was speaking on 10 June about revenue collected since the start of the financial year, 21 December 2020 (see report on Tolonews. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | The exceptions to this exclusion are so rare that AAN wrote up this 2020 case study of a Shia Hazara Taleban shadow district governor in Sar-e Pul province). Typically, there are very local political reasons behind such unusual moves. |

| ↑3 | There are no official sources on the district population’s ethnic composition. According to locals interviewed for this 2019 AAN report, it is a mixture of Shia and Sunni Hazaras, Sunni Pashtuns, Sunni Tajiks, as well as a small Shia Uzbek community. Pashtuns live mainly in Zaiwalat, Hazaras and Sayeds in Sarchashma and Sanglakh, and Tajiks mostly live in Takana and the district centre. The Shia Uzbek community in Sarchashma has been integrated into the local Shia Hazara community. Because of the way the mujahedin originally mobilised, factions and frontlines in Jalrez as in the rest of Afghanistan have typically followed ethnic cleavages |

| ↑4 | For a description of part of the southern part of this road in happier times, see our travelogue from 2013. |

| ↑5 | In late 2018, the Taleban made incursions into both Malestan and Jaghori districts, but were pushed back (see AAN reporting here and here. |

| ↑6 | There has also been reporting of the government’s failure to concede areas it could not hold earlier, when there was still time to regroup, a move which could have left the ANSF in more defendable positions, with better protected troops and supply lines. See this article by The Guardian’s Emma Graham-Harrison. |

Revisions:

This article was last updated on 16 Jul 2021

Verknüpfte Dokumente

- Dokument-ID 2057178 Hat folgenden Nachtrag

Lagekarte: Landkarte mit Verwaltungseinheiten (Distriktebene) zu Veränderungen in der Kontrolle von Distriktzentren (Berichtszeitraum 1. Mai bis 14. Juli 2021)

Changes in district centre control 1 May - 14 July 2021 (Landkarte oder Infografik, Englisch)