Country Briefing

| Area: | 652.230 km² |

| Capital: | Kabul |

| Population: | ca. 40.1 million (2024 est.) |

| Official languages: | Dari and Pashto [1] |

| Currency: | Afghani (Af)[2] |

1. BRIEF OVERVIEW OF AFGHANISTAN

Afghanistan is a landlocked country in the heart of southern Central Asia, largely characterised by the Hindu Kush mountain range.[1] It is one of the poorest countries in the world[2] , with almost half of the population in need of humanitarian aid.[3] (-> ecoi.net search on poverty).

Much of the country is arid or semi-arid. About one-eighth of the country's total area is arable land, of which only about half is cultivated. Agriculture and livestock farming are normally the most important elements of the gross domestic product, together accounting for almost half of it, although the destruction caused by the war has driven many people out of rural areas and accelerated urbanisation.[4]

Approximately half of Afghan men are literate, while only 16 per cent of women in rural areas and 40 per cent of women in urban areas are literate [5] (-> ecoi.net search for literacy rate).

The Taliban, who returned to power in 2021, have suspended all civil and political rights and banned any criticism of their rule. Women and religious and ethnic minorities are most severely affected by the restrictions on freedom. The population is suffering from an economic and humanitarian crisis. [6]

2. HISTORY[11]

The borders of modern-day Afghanistan were established in the 19th century during the conflict between Tsarist Russia and the British Empire, known as the "Great Game".[8] In 1973, the Republic of Afghanistan was proclaimed, succeeding a monarchical system, and in 1978 it was replaced by the Democratic Republic of Afghanistan through a coup d'état, which ushered in a communist phase.[9] In 1979, the Soviet Union invaded Afghanistan to support the communist Afghan government in its conflict with Muslim guerrillas.[10] Resistance to the Soviet forces formed, and Islam was built up as the ideological antithesis of communism.[11] By 1980, several regional groups known as the mujahideen ("those who participate in jihad") had joined forces against the Soviet invaders and the Afghan army they supported. The mujahideen were supported financially and militarily by the United States, Pakistan, China, European and Arab states. When Soviet troops left the country in 1989, civil war continued between the mujahideen and the communist Afghan government, which was finally deposed in 1992 following the collapse of the Soviet Union and the resulting loss of support. A coalition consisting mainly of the mujahideen who had previously fought the Soviet Union established a transitional government.[12] The rule of the mujahideen, who attempted to monopolise power, ended in civil war.[13] Afghanistan was de facto ruled by militia leaders and warlords, and the population suffered from road taxes, extortion and kidnappings. Partly in response to this situation, the Taliban ("religious students"[14] ) formed in the autumn of 1994, recruiting from madrasa students in Pakistan and the province of Kandahar.[15]

In 1996, the Taliban finally captured Kabul and by 2001 they had gained control of more than 90 per cent of the country. Pakistan, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates formally recognised the Taliban government after the fall of Kabul, but it was criticised for its extreme views – particularly regarding women – and its human rights record.[16] When the Taliban refused to hand over Osama Bin Laden, who was staying in Afghanistan and was held responsible by the US for the attacks on the World Trade Centre and the Pentagon, the US attacked the Taliban in 2001, whose resistance collapsed within a few days. A transitional government was installed. In 2004, democratic presidential elections were held, in which women also had the right to vote, and Hamid Karzai emerged victorious. Attacks and violent clashes between the US-led coalition, later NATO troops, and Taliban forces continued in the following years, and the number of civilian casualties remained high. In 2018 and 2019, peace talks were held between the Taliban and the United States, Saudi Arabia and Pakistan. In an agreement reached in February 2020, the United States proposed withdrawing its troops on the condition that the Taliban engage in peace negotiations with the Afghan government and prohibit Al-Qaeda and Islamic State from operating in Afghanistan. However, negotiations between the Taliban and the central government made little progress, even when the United States resumed the withdrawal of its troops in May 2021 after several months of delay.[17] In early summer 2021, the Taliban finally captured large parts of Afghanistan, including the capital Kabul in August 2021.[18] In September 2021, the Taliban formed an interim government with exclusively male members, mainly of Pashtun origin.[19] The "Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan" has been seeking international recognition since 2021[20] , but so far only Russia has recognised the Taliban government.[21] The term "de facto government" has become established.[22] The Taliban leader exercises unrestricted political power and rules by decree.[23]

The ACCORD thematic dossier provides information on life under the renewed Taliban rule in Afghanistan:

- ACCORD – Austrian Centre for Country of Origin and Asylum Research and Documentation: ecoi.net featured topic on Afghanistan: Overview of current developments in Afghanistan, 17 October 2025

Further reading

The following article by the Federal Agency for Civic Education provides a good overview of Afghan history:

In German:

- BpB – Federal Agency for Civic Education: Afghanistan – Afghanistan – Geschichte, Politik, Gesellschaft, 15 October 2018

The online encyclopaedia Encyclopaedia Britannica provides comprehensive information on the history of Afghanistan from early history to the present day:

- Encyclopaedia Britannica: Afghanistan, History, last updated 20 August 2025

https://www.britannica.com/place/Afghanistan/The-arts-and-cultural-institutions#ref21380

3. ETHNIC AND RELIGIOUS GROUPS

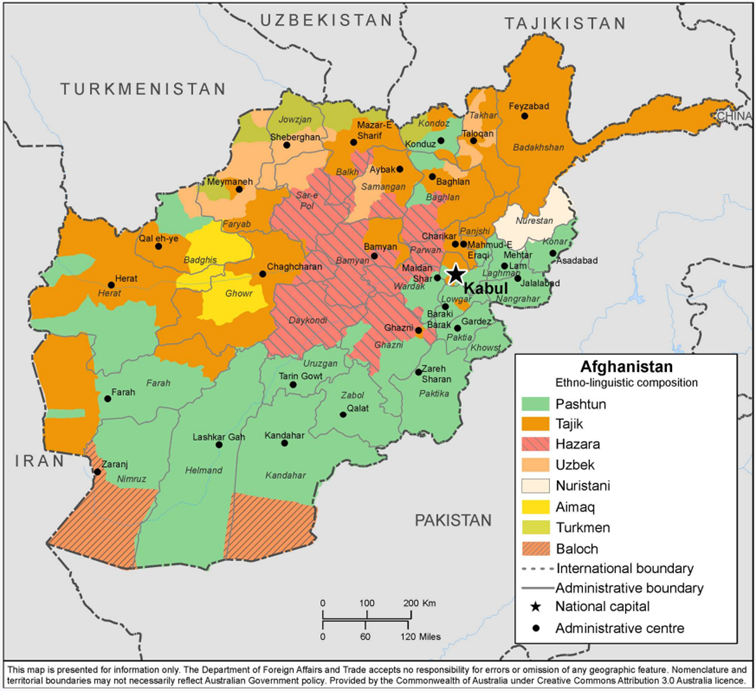

The largest ethnic group in Afghanistan[24] are the Pashtuns (approx. 42 per cent of the Afghan population), followed by Tajiks (approx. 27 per cent), Hazaras (approx. 9 per cent) and Uzbeks (approx. 9 per cent). In addition to these large and larger ethnic groups, there are also numerous small groups, peoples and tribes, such as the Aimak, Baloch and Nuristani.[25]

(Source: DFAT, 14 January 2022)[26]

Approximately 98 to 99 per cent of Afghans are Muslim[27] , of whom over 80 per cent are Sunni Muslims.[28] Non-Muslim minorities such as Sikhs and Hindus have shrunk to a small fraction of their former size, as most have emigrated in recent decades.[29] Only a few thousand[30] or even a few hundred of them remain in Afghanistan[31] . Most Taliban members are ethnic Pashtuns, but they are also supported by members of other ethnic groups.[32] The new Taliban government does not represent the country's population; it is composed exclusively of men, almost all of whom are Taliban, and is dominated by Pashtuns.[33]

Pashtuns are the largest ethnic group in Afghanistan, but they do not form a homogeneous group; rather, they are divided into different tribes and sub-tribes. Pashtuns mainly live in the south and east of the country,[34] but also in other regions of Afghanistan.[35] The Pashtunwali, a system of values and behaviour that has been passed down orally for centuries, is still important to Pashtuns today. It governs the behaviour of both individuals and groups[36] and is a mixture of a tribal code of honour and local interpretations of Sharia law.[37] Although the majority of Pashtuns have led a sedentary life for centuries, aspects of their former nomadic way of life (culture of honour) can be traced back to the Pashtunwali.[38] In the event of disputes or matters of interest to the group, the tribal council is convened to resolve issues and make decisions.[39] Disputes among Pashtuns are traditionally attributed to "zar, zan and zamin" (gold, women and land), the most important foundations of wealth and honour in tribal society.[40] According to this proverb, women are considered a cause of dispute and at the same time equated with property.[41] Women are shielded from all matters outside the home and are required to wear a full-face veil ( ) and full-body covering (burqa).[42] Pashtuns have always dominated the country's political scene. [43]

After the Pashtuns, the Tajiks are the second largest ethnic group in Afghanistan[44] and live mainly in the north and north-east of the country[45] . Most Tajiks are Dari-speaking Sunni Muslims, but a minority professes Twelver Shi'ism.[46] Tajiks are not divided into clearly defined tribes,[47] loyalties arise through family and village. Afghanistan was ruled by Tajiks for two short periods. [48]

The Hazara are an ethnolinguistic group from the mountainous region of central Afghanistan.[49] Hazara traditionally speak a dialect of Dari called Hazaragi. The vast majority are followers of Twelver Shia Islam, a smaller number are Ismailis, and a minority profess Sunni Islam. Before the 19th century, the Hazara were the ethnic majority in Afghanistan[50] and until 1890 they were largely autonomous[51] . Their violent and brutal integration into the emerging Afghan state by predominantly Pashtun armies[52] (according to some estimates, more than half of all Hazaras were killed by 1893)[53] laid the foundation for lasting hostility between the Shiite Hazaras and the Sunni Pashtuns, both for religious and ethnic reasons. Since then, according to Encyclopaedia Britannica, they have been victims of persecution, displacement and marginalisation.[54]

Uzbeks speak a Turkic language and are predominantly Sunni Muslims. Uzbeks and Turkmen inhabit most of the fertile land in northern Afghanistan and live mainly from agriculture. Uzbeks have tribal identities that still largely determine the structures within their respective societies. [55]

Further reading

In English: Minority Rights Group International (MRG) provides information on the above and other ethnic minorities in Afghanistan:

- MRG – Minority Rights Group International: Afghanistan, last updated December 2021

https://minorityrights.org/country/afghanistan/

4. WOMEN

According to the Women, Peace and Security Index[56] 2023/24, which attempts to provide information on the social status and degree of self-determination of women in countries around the world,[57] Afghanistan ranks last out of a total of 177 countries.[58] According to the UN Human Rights Council, the large-scale, systematic violation of the fundamental rights of women and girls in Afghanistan by the Taliban's policies following their recent takeover in August 2021 constitutes persecution based on gender and institutionalised gender apartheid.[59] (-> ecoi.net search on women's rights) (-> ecoi.net search on women and girls)

The US-based non-governmental organisation Freedom House reports that the Taliban has ended the limited formal protection against domestic violence that the republic had offered (-> ecoi.net search on domestic violence). Shelters for survivors of gender-based violence (GBV) were closed by the Taliban and some residents were reportedly taken to prisons (-> ecoi.net search on gender-based violence). Individuals who had been convicted of gender-based violence were released by the Taliban during their takeover. [60] Domestic violence and forced marraiges are widespread, and the suicide rate among women in Afghanistan is among the highest in the world. [61]

After the fall of the Taliban in 2001, several measures were taken to improve the situation of Afghan women and girls, resulting in an improvement in access to education and employment, and in political representation [62] . The life expectancy of women also increased significantly after the fall of the Taliban, by 10 years between 2001 and 2017..[63] However, the average education of Afghan women was still alarmingly low, at only two years [64] . In March 2022, the de facto government banned girls from attending school beyond the 6th grade. Since December 2022, women have been banned from higher education, and since 2024 they have also been barred from attending public or private medical institutions, thus depriving them of their last opportunity to pursue university-level studies.[65] (-> ecoi.net search on women and education)

A ministry for the "promotion of virtue and prevention of vice" moved into the building of the former Ministry of Women's Affairs, with offices for the religious morality police.[66] In August 2024, the de facto government announced a "law for the propagation of virtue and prevention of vice" with the aim of implementing its vision of a purely Islamic system nationwide. This law incorporated many guidelines previously issued in the form of decrees, while others were expanded and new ones added. For example, women must wear a hijab outside the home, unrelated men and women are prohibited from looking at each other, drivers may only transport women accompanied by a mahram, a male guardian, and women are also prohibited from using public transport without a mahram. [67] The law is enforced by Taliban officials.[68] The UN Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW) CEDAW) reports that between November 2022 and May 2023, 58 women were publicly flogged for alleged adultery, non-compliance with dress codes, fleeing their parents' home or shopping without a mahram. Furthermore, 37 stoning sentences have been handed down against women since 2022.[69]

All Afghan girls and women suffer from the Taliban's policy of persecution; the situation is even more serious for women and girls in remote and rural areas, especially if they belong to minorities or marginalised groups.[70] (-> ecoi.net search on forced marriage). [71]

Detailed and continuously updated information on decisions taken under the new Taliban regime concerning women and girls, as well as on the general situation of women in Afghanistan, is available in the ACCORD thematic dossier:

- ACCORD – Austrian Centre for Country of Origin and Asylum Research and Documentation: ecoi.net featured topic on Afghanistan: Overview of recent developments in Afghanistan, 17 October 2025

Bibliography

In English: On 7 July 2025, the UN Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW) published its concluding observations on the state report on the implementation of the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women:

- CEDAW - UN Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination Against Women: Concluding observations on the fourth periodic report of Afghanistan [CEDAW/C/AFG/CO/4], 7 July 2025

https://www.ecoi.net/en/file/local/2128194/CEDAW_C_AFG_CO_4_63684_E.docx

In February 2025, ACCORD published a report based on interviews on the impact of legal, administrative and social restrictions on the human rights situation in the country, particularly on women and girls:

- ACCORD - Austrian Centre for Country of Origin and Asylum Research and Documentation: Afghanistan: Report on the impact of the Taliban's information practices and legal policies, particularly on women and girls, February 2025

https://www.ecoi.net/en/file/local/2122510/ACCORD_Afghanistan_February_2025_FINAL.pdf

The German Federal Office for Migration and Refugees addresses the situation of women in Afghanistan between 1996 and 2023 in a country report:

- BAMF – Federal Office for Migration and Refugees: Länderreport 57; Afghanistan: Die Situation von Frauen, 1996 - 2023 (Stand: 02/2023), February 2023

- https://www.ecoi.net/en/document/2069072.html

5. HUMANITARIAN SITUATION

After 40 years of war, even before the Taliban regained power in August 2021, the humanitarian situation was characterised by increasing hunger, economic decline, rising prices for food and other essential goods, and growing poverty.[72] After the Taliban regained power, a new period began, characterised by rapid economic decline, famine and the risk of malnutrition, as well as rising inflation, an increase in both urban and rural poverty, and the near collapse of the national health system.[73] Although, according to the World Food Programme (WFP), the situation has improved compared to the period following the political transition in 2021, 14.8 million Afghans were affected by food insecurity in 2024. At the end of 2024, one in three people were still suffering from food-related hardship and more than three million were affected by acute famine. The WFP predicts a food crisis in 2025, which will leave 3.5 million children under the age of five and over a million pregnant and breastfeeding women suffering from acute malnutrition, among others.[74] Food insecurity is mainly due to a fragile economy, significant cuts in humanitarian aid and environmental disasters, particularly floods and droughts.[75] In October 2023, thousands of people were killed in a series of earthquakes. In April and May 2024, repeated flooding and mudslides in the north and west of the country killed hundreds of people and devastated villages and tens of thousands of hectares of farmland. Afghanistan has limited infrastructure and resources to respond to such events.[76] (-> ecoi.net search on food insecurity in Afghanistan) (-> ecoi.net search on humanitarian aid).[77]

Bibliography

In English: A report published in December 2023 by the European Asylum Agency (EUAA) deals in Chapter 3 with the humanitarian situation in Afghanistan up to and including September 2023:

- EUAA – European Union Agency for Asylum (formerly: European Asylum Support Office, EASO): Afghanistan Country Focus, December 2023

https://www.ecoi.net/en/file/local/2101835/2023_12_EUAA_COI_Report_Afghanistan_Country_Focus.pdf

In English: A report published in November 2023 by CARE International and other organisations addresses the humanitarian situation in Afghanistan with a focus on women:

- CARE International et al.: Afghanistan Rapid Gender Analysis 2023, November 2023

https://reliefweb.int/attachments/8d662021-dd63-4c3c-a7bb-ae3a61b2fc6a/Rapid%20Gender%20Analysis%20Afghanistan%202023-GiHA%20WG.pdf

6. Internally displaced persons and returnees from abroad

According to the IOM, a total of approximately 6.6 million people became internally displaced within Afghanistan in the ten years from 2012 to 2022[78] , with almost 40 per cent of these displacements due to environmental disasters and 60 per cent due to conflicts[79] . Between 2021 and 2025, the figure was approximately 3.1 million people. In 2025, the main triggers were environmental disasters: people fled drought, floods and other disasters.[80] The scarcity of land and housing makes it impossible for many internally displaced persons to return. There is a lack of sustainable employment opportunities in their places of origin. The return of Afghan refugees from abroad further exacerbates the socio-economic challenges for internally displaced persons. [81]

In a survey conducted in 2021, 40 per cent of the IDP households surveyed reported insecure tenure in their current accommodation. For example, they had no or only a verbal tenancy agreement and were constantly at risk of possible eviction..[82] Data from 2021 shows that around 58 per cent of IDPs are children, while the remaining 42 per cent are half men and half women.[83] (-> ecoi.net search on internally displaced persons).

In 2022, there were approximately 5.7 million refugees from Afghanistan worldwide, around 90 per cent of whom were in the two neighbouring countries of Iran (approximately 3.4 million) and Pakistan (approximately 1.7 million).[84] As of February 2024, the IOM counted a total of approximately 5.2 million returnees in Afghanistan.[85] In October 2023, the Pakistani government announced a return plan for "illegal aliens"[86] . In spring 2025, Iranian authorities set a deadline for all Afghans without residence permits to leave Iran.[87] According to figures from the International Organisation for Migration (IOM), more than four million Afghans returned from Pakistan and Iran between September 2023 and August 2025,[88] with 1.9 million returning in the first seven months of 2025 alone.[89] The returnees are putting pressure on the communities where they settle, which already lacked basic services and economic avenues. The vast majority of Afghan returnees also have no documents, which makes it difficult for them to obtain identity papers, access public services and receive official assistance.[90] Many of the returnees have nowhere to return to and no social network, as they have never lived in Afghanistan; more than half of them are under the age of 18.[91] (-> ecoi.net search on returnees).

7. Recent takeover by the Taliban in 2021

In the first few months of 2021, an unprecedented number of civilians were killed and injured in Afghanistan, and at least 560,000 people were displaced.[92] Various sources documented serious human rights violations by the Taliban during their advance, including summary executions and retaliatory killings of civilians and government employees.[93]

With the Taliban's increasing territorial control over Afghanistan in August 2021, conflict-related security incidents decreased significantly,[94] with the United Nations recording a 91 per cent decrease in security incidents between August and December 2021 compared to the previous year.[95]

Despite the Taliban’s announcement of a general amnesty for former government employees and former members of the security forces, and despite assurances from the Taliban leadership that they would hold their troops accountable for violations of the amnesty,[96] various sources reported human rights violations in October and November 2021, including unlawful killings[97] , summary executions and enforced disappearances[98] , as well as abuses of people who had "collaborated with foreigners".[99]

Further reading

The ACCORD thematic dossier provides information on current developments in Afghanistan since the Taliban's recent takeover:

- ACCORD – Austrian Centre for Country of Origin and Asylum Research and Documentation: ecoi.net featured topic dossier on Afghanistan: Overview of current developments and key actors in Afghanistan, 17 October 2024

8. Key actors

a. Taliban

According to Afghanistan expert Thomas Ruttig, the structure of the Taliban has a vertical, horizontal and centralist dimension. The centralised dimension is represented by the position of the Amir ul-Muminin, who can make far-reaching decisions single-handedly and revoke any decision made by the hierarchical levels below him without any other authority being able to oppose him. The Amir ul-Muminin is appointed for life; there is no direct succession mechanism. The successor is appointed by a kind of consensus decision of the Taliban leadership.[100] Hibatullah Achundsada, one of the deputies of the previous leader Akhtar Mohammad Mansour, was appointed the new Taliban leader in 2016.[101]

According to Thomas Ruttig, there is rivalry between two large regional networks within the Taliban movement over positions and power. The largest network is the Kandahar Taliban from southern Afghanistan, the region from where the Taliban historically originated and where Amir ul-Muminin Hibatullah Achundsada hails from. According to Ruttig, the Kandahari Taliban are the numerically superior network. The second network is the Haqqani network, which is associated with the south-east of the country and is much smaller. The leader of the network is Sirajuddin Haqqani, one of the three deputy Taliban leaders. The other two Taliban leaders, Mulla Yaqub and Mulla Abdul Ghani (Baradar), are Kandaharis. According to some sources, the Haqqani network had greatly increased its influence in the period before the new takeover, while the Kandahari Taliban are now consolidating their power and expanding at the expense of the Haqqanis, according to Ruttig.[102]

Despite increasing internal tensions and differences of opinion[103] , the Taliban emphasise their unity and the authority of their leader Hibatullah Achundsada.[104] The internal tensions mainly run along a dividing line between hardliners and moderates. The moderates include long-standing Taliban members who believe that relations with foreign partners must at least be kept functional and that Afghanistan must be integrated into the international system, particularly the global financial system. The hardliners take a more ideological approach and focus less on international relations.[105] Achundsada has so far withstood pressure to take a more moderate line. There were reportedly no signs that other Taliban leaders based in Kabul could have a lasting impact on governance. According to the UN Security Council, there was little prospect of change in the medium to short term. [106]

Further reading

Detailed information on the structures and various factions within the Taliban can be found in the report on the COI webinar with Katja Mielke and Emran Feroz (in German):

- ACCORD – Austrian Centre for Country of Origin and Asylum Research and Documentation: Afghanistan: Aktuelle Lage & Überblick über relevante Akteure; Situation gefährdeter Gruppen, March 2022

https://www.ecoi.net/en/file/local/2070441/2022-03_ACCORD_COI-Webinar_Afghanistan_Februar_2022.pdf

In English: A conference report by the Danish Refugee Council (DRC) from December 2022 also contains information on the structures of the Taliban, among other topics:

- DRC – Danish Refugee Council: Afghanistan conference; The Human Rights Situation after August 2021, 30 December 2022

https://asyl.drc.ngo/media/13vhsflb/drc-afghanistan-conference-report-28nov2022.pdf

In English: A report by the Institute for the Study of War (ISW) from March 2024 contains information on Taliban policy from 2021 to 2024, including structures within the Taliban:

- ISW – Institute for the Study of War: Taliban Governance in Afghanistan, March 2024

b. Haqqani network

In September 2021, the BBC described the Haqqani Network (HQN) as a militant group linked to the Taliban and responsible for some of the deadliest attacks in the country's war between 2001 and 2021. Unlike the Taliban, the Haqqani Network has been put on the list of foreign terrorist organisations by the United States.[107]

The Haqqani Network (HQN) was formed in the late 1980s, around the time of the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan. The founder of the HQN, Jalaluddin Haqqani, established relations with Osama Bin Laden in the mid-1980s and joined the Taliban in 1995. After the fall of the Taliban in 2001, Haqqani retreated to Pakistan, from where the HQN continued to plan and carry out terrorist operations in Afghanistan under the leadership of his son Sirajuddin. In 2015, Sirajuddin Haqqani was appointed deputy head of the Taliban.[108]

Since the Taliban took power in Afghanistan in August 2021, the HQN has occupied important posts within the de facto Taliban government,[109] with Sirajuddin Haqqani as the Taliban's Minister of Interior.[110] HQN controls key areas such as home affairs, the intelligence, passports and migration, and, as of May 2022, much of security in Afghanistan, including in the capital Kabul.[111] USDOS noted in 2022 that the HQN is believed to comprise around 3,000 to 5,000 fighters operating in Afghanistan and Pakistan.[112] The Haqqani Network reportedly maintains close links with Al-Qaeda[113] and the Pakistani Taliban (Tehrik-e Taliban Pakistan, TTP). [114]

c. Al-Qaeda

According to the UN Security Council, the Taliban and Al-Qaeda maintain close relations even after the Taliban's renewed takeover of power. Security Council member states estimate that Al-Qaeda has been granted a safe haven under the Taliban and has greater room for manoeuvre.[115] As reported in July 2023, Al-Qaeda in Afghanistan operates largely underground to support the Taliban's narrative that they are abiding by agreements not to make Afghan territory available for terrorist purposes. Under the auspices of senior Taliban leaders, Al-Qaeda members infiltrated legal institutions and government agencies, thus ensuring the nationwide expansion of Al-Qaeda cells. The core of Al-Qaeda in Afghanistan remained stable with 30 to 60 members, while the total number of Al-Qaeda fighters in Afghanistan is estimated at around 400 .[116] According to a report published by the United Nations Security Council (UNSC) in February 2025, there has been no change in Al-Qaeda's status or strength.[117]

d. Islamic State in Khorasan Province (ISKP)

The Islamic State in Khorasan Province (ISKP), an offshoot of the Islamic State group that has been active in Afghanistan since mid-2014,[118] is the main antagonist of the Taliban[119] and the greatest terrorist threat in Afghanistan and the wider region.[120] The group is mainly made up of former members of the Tehrik-e Taliban Pakistan, the Afghan Taliban and the Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan. For 2022, the USDOS estimated the group's strength at around 2,000 fighters.[121]

ISKP attacks against both the Taliban and international targets became increasingly sophisticated. The group's strategy was to conduct public attacks in particular to undermine the Taliban's ability to provide security. In general, ISKP attacks indicated strong operational capabilities.[122] ISKP poses a particular threat to certain population groups, such as Hazaras. Around 2015, the ISKP began attacking mosques, hospitals, schools and other civilian facilities, particularly in Shia neighbourhoods. In the past, the ISKP has also attacked journalists, civil society activists, health workers and, in particular, girls' schools.[123] According to the February 2025 report published by the UNSC, ISKP poses the greatest threat to the de facto authorities, ethnic and religious minorities and international representatives in Afghanistan, despite the measures taken against it by the Taliban.[124]

e. Resistance groups

The National Resistance Front (NRF) and the Afghanistan Freedom Front (AFF) are armed groups that were formed after the Taliban captured Kabul and are led by former officers of the Afghan National Security Forces (ANSF) and former Afghan government officials. The NRF operates mainly in the Tajik-dominated north-east, while the AFF also operates in the north-east and south of the country. Both groups aim to overthrow the Taliban and establish an Afghan republic. [125][126]According to Ahmad Massoud, leader of the National Resistance Front (NRF), the NRF, the largest resistance group operating mainly in north-eastern Afghanistan, had over 4,000 fighters as of September 2023, who mainly engage in guerrilla warfare. [127]

[1] Encyclopaedia Britannica: Afghanistan – Country, Afghanistan – Introduction & Quick Facts, last updated 20 August 2025, https://www.britannica.com/place/Afghanistan

[2] Wirtschaftswoche: These are the poorest countries in the world according to GDP per capita, 11 March 2025, https://www.wiwo.de/politik/ausland/ranking-2025-das-sind-die-aermsten-laender-der-welt-nach-bip-pro-kopf-/26792056.html; World Population Review: Poorest Countries in the World 2025, 2025, https://worldpopulationreview.com/country-rankings/poorest-countries-in-the-world#title

[3] HRC - UN Human Rights Council (formerly UN Commission on Human Rights): Access to justice and protection for women and girls and the impact of multiple and intersecting forms of discrimination; Report of the Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights in Afghanistan, Richard Bennett [A/HRC/59/25], 16 June 2025, https://www.ecoi.net/en/file/local/2127745/g2508942.pdfp. 15

[4] Encyclopaedia Britannica: Afghanistan, Economy, last updated 20 August 2025, https://www.britannica.com/place/Afghanistan/Agriculture-and-forestry

[5] UN OCHA – UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs: Afghanistan Humanitarian Needs Overview 2023 (January 2023), January 2023, https://reliefweb.int/attachments/2f525ec0-622e-47ee-bb0b-d411323dc054/AFG-HNO-2023-v06.pdf, S. 42

[6] Freedom House: Freedom in the World 2025, Afghanistan, 2025, https://www.ecoi.net/de/dokument/2129004.html overview

[7] The historical overview is based primarily on information from the Encyclopaedia Britannica.

[8] Encyclopaedia Britannica: Afghanistan – Introduction & Quick Facts, last updated 20 August 2025,https://www.britannica.com/place/Afghanistan

[9] Encyclopaedia Britannica: Afghanistan – History, Afghanistan since 1973, last updated 20 August 2025, https://www.britannica.com/place/Afghanistan/Mohammad-Zahir-Shah-1933-73#ref21410

[10] Encyclopaedia Britannica: Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, last updated 4 July 2025, https://www.britannica.com/event/Soviet-invasion-of-Afghanistan

[11] FES – Friedrich Ebert Foundation: Afghanistan between chaos and power politics, April 1998, https://www.fes.de/ipg/ipg2_98/artschetter.html

[12] Encyclopaedia Britannica, Afghanistan – History, Afghanistan since 1973, last updated 20 August 2025, https://www.britannica.com/place/Afghanistan/Mohammad-Zahir-Shah-1933-73#ref21410

[13] BpB – Federal Agency for Civic Education: Afghanistan, 27 January 2022, https://www.bpb.de/themen/kriege-konflikte/innerstaatliche-konflikte/155323/afghanistan/#node-content-title-3

[14] BpB – Federal Agency for Civic Education: We also served Germany – On cooperation with Afghan local staff during the ISAF mission, 2018, https://www.bpb.de/system/files/dokument_pdf/10298_Wir_dienten_Deutschland_Leseprobe.pdf, p. 21

[15] Encyclopaedia Britannica, Afghanistan – History, Afghanistan since 1973, last updated 20 August 2025, https://www.britannica.com/place/Afghanistan/Civil-war-mujahideen-Taliban-phase-1992-2001

[16] Encyclopaedia Britannica: Afghanistan – History, Afghanistan since 1973, last updated 20 August 2025, https://www.britannica.com/place/Afghanistan/Civil-war-mujahideen-Taliban-phase-1992-2001

[17] Encyclopaedia Britannica: Afghanistan – History, Struggle for democracy, last updated 20 August 2025, https://www.britannica.com/place/Afghanistan/Struggle-for-democracy

[18] SWP – German Institute and Centre for International and Security Affairs: Zentralasiens Muslime und die Taliban

, February 2022, https://www.swp-berlin.org/publications/products/aktuell/2022A15_Zentralasien_MuslimeTaliban.pdf

[19] AP – Associated Press: Taliban form all-male Afghan government of old guard members, 8 September 2021, https://apnews.com/article/middle-east-pakistan-afghanistan-arrests-islamabad-d50b1b490d27d32eb20cc11b77c12c87

[20] BpB: Afghanistan, 9 July 2024, https://www.bpb.de/themen/kriege-konflikte/dossier-kriege-konflikte/155323/afghanistan/

[21] DW – Deutsche Welle: Erfolg für Taliban: Moskau erkennt Regierung in Kabul an, 4 July 2025, https://www.dw.com/de/erfolg-f%C3%BCr-taliban-moskau-erkennt-regierung-in-kabul-an/a-73152424

[22] Scientific Services of the German Bundestag:

Zur völkerrechtlichen Anerkennung des Taliban-Regimes in

Afghanistan, 24 February 2022, https://www.bundestag.de/resource/blob/883014/2134fb17906b58cd472adc29a38e2e54/voelkerrechtlichen-Anerkennung-des-Taliban-Afghanistan-data.pdf (The Taliban in Afghanistan), p. 26

[23] Freedom House: Freedom in the World 2025 – Afghanistan, 2025

https://www.ecoi.net/de/dokument/2129004.html overview

[24] No reliable data on the proportion of ethnic groups in the total population can be provided for Afghanistan, as the last partial census was conducted in 1979. Encyclopedia Britannica, Afghanistan, People, last updated 20 August 2025, https://www.britannica.com/place/Afghanistan/Plant-and-animal-life#ref21423

[25] Encyclopedia Britannica: Afghanistan, People, last updated 20 August 2025, https://www.britannica.com/place/Afghanistan/Plant-and-animal-life#ref21423

[26] DFAT – Australian Government - Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade: DFAT Thematic Report on Political and Security Developments in Afghanistan (August 2021 to January 2022), 14 January 2022,

https://www.ecoi.net/en/file/local/2067344/country-information-report-afghanistan.pdfp. 1

[27] Political Handbook of the World, 2018-2019, SAGE Publications (edited by Tom Lansford), 2019 (Kindle edition), p. 3; MRG – Minority Rights Group International: Afghanistan – Communities, last updated December 2021, https://minorityrights.org/country/afghanistan/

[28] Encyclopaedia Britannica: Afghanistan – People, Religion, last updated 20 August 2025, https://www.britannica.com/place/Afghanistan/Languages#ref21425

[29] Freedom House: Freedom in the World 2021 – Afghanistan, 4 March 2021, https://www.ecoi.net/en/document/2068626.html

[30] Encyclopaedia Britannica: Afghanistan - People, Religion, last updated 20 August 2025, https://www.britannica.com/place/Afghanistan/Languages

[31] MRG – Minority Rights Group International: Afghanistan – Communities, last updated December 2021, https://minorityrights.org/country/afghanistan/

[32] Freedom House: Freedom in the World 2022 – Afghanistan, 28 February 2022, https://www.ecoi.net/en/document/2068625.html, section B4

[33] AAN – Afghanistan Analysts Network: Afghanistan’s conflict in 2021 (2): Republic collapse and Taleban victory in the long-view of history, 12 January 2022, https://www.ecoi.net/de/dokument/2066639.html

[34] MRG – Minority Rights Group International: Pashtuns in Afghanistan, no date, https://minorityrights.org/minorities/pashtuns/

[35] Encyclopedia Britannica, Afghanistan, People, last updated 20 August 2025, https://www.britannica.com/place/Afghanistan/Plant-and-animal-life#ref21423

[36] Rzehak, Lutz: Doing Pashto, Pashtunwali as the ideal of honourable behaviour and tribal life among the Pashtuns, AAN (ed.), March 2011, https://www.afghanistan-analysts.org/wp-content/uploads/downloads/2012/10/20110321LR-Pashtunwali-FINAL.pdf, p. 1

[37] MRG – Minority Rights Group International: Pashtuns in Afghanistan, no date, https://minorityrights.org/minorities/pashtuns/

[38] Rzehak, Lutz: Doing Pashto, Pashtunwali as the ideal of honourable behaviour and tribal life among the Pashtuns, AAN (ed.), March 2011, https://www.afghanistan-analysts.org/wp-content/uploads/downloads/2012/10/20110321LR-Pashtunwali-FINAL.pdf, p. 1

[39] MRG – Minority Rights Group International: Pashtuns in Afghanistan, no date, https://minorityrights.org/minorities/pashtuns/; Rzehak, Lutz: Doing Pashto, Pashtunwali as the ideal of honourable behaviour and tribal life among the Pashtuns, AAN (ed.), March 2011, https://www.afghanistan-analysts.org/wp-content/uploads/downloads/2012/10/20110321LR-Pashtunwali-FINAL.pdf, pp. 13-14

[40] USIP – United States Institute of Peace: The Clash of Two Goods, State and Non-State Dispute Resolution in Afghanistan, November 2006, https://www.usip.org/sites/default/files/file/clash_two_goods.pdf, p. 8

[41] Shoro, Shahnaz: Honour Killing in the Second Decade of the 21st Century, 2017 (available at https://www.ebsco.com/), p. 43

[42] MRG – Minority Rights Group International: Pashtuns in Afghanistan, no date, https://minorityrights.org/minorities/pashtuns/

[43] MRG – Minority Rights Group International: Afghanistan, Communities, last updated December 2021, https://minorityrights.org/country/afghanistan/

[44] MRG – Minority Rights Group International: Afghanistan, Tajiks, no date, https://minorityrights.org/minorities/tajiks/

[45] MRG – Minority Rights International: Afghanistan, Communities, last updated December 2021, https://minorityrights.org/country/afghanistan/

[46] MRG – Minority Rights Group International: Afghanistan, Tajiks, no date, https://minorityrights.org/minorities/tajiks/

[47] Encyclopaedia Britannica, Afghanistan – People, last updated on 22 January 2024, https://www.britannica.com/place/Afghanistan

[48] MRG – Minority Rights Group International: Afghanistan, Tajiks, no date, https://minorityrights.org/minorities/tajiks/

[49] Encyclopaedia Britannica: Hazara, last updated 21 December 2023, https://www.britannica.com/topic/Hazara

[50] MRG – Minority Rights Group International: Hazaras in Afghanistan, last updated in December 2021, https://minorityrights.org/minorities/hazaras/

[51] Encyclopaedia Britannica: Hazara, last updated 21 December 2023, https://www.britannica.com/topic/Hazara

[52] Encyclopaedia Britannica: Hazara, last updated 21 December 2023, https://www.britannica.com/topic/Hazara

[53] MRG – Minority Rights Group International: Hazaras in Afghanistan, last updated in December 2021, https://minorityrights.org/minorities/hazaras/

[54] Encyclopaedia Britannica: Hazara, last updated 21 December 2023, https://www.britannica.com/topic/Hazara

[55] MRG – Minority Rights Group International: Afghanistan, Uzbeks and Turkmens in Afghanistan, no date, https://minorityrights.org/minorities/uzbeks-and-turkmens/

[56] The Women, Peace and Security Index is compiled annually by Georgetown University's Institute for Women, Peace and Security. This index assesses countries using indicators designed to measure women's equality and autonomy, such as educational attainment, financial independence, political representation, legal discrimination and intimate partner violence. (GIWPS – Georgetown Institute for Women, Peace and Security: Women Peace and Security Index 2023/24, https://giwps.georgetown.edu/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/WPS-Index-full-report.pdf, p. 16)

[57] GIWPS – Georgetown Institute for Women, Peace and Security: Women Peace and Security Index 2023/24, https://giwps.georgetown.edu/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/WPS-Index-full-report.pdf, p. 1

[58] GIWPS – Georgetown Institute for Women, Peace and Security: Women Peace and Security Index 2023/24, https://giwps.georgetown.edu/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/WPS-Index-full-report.pdf, p. i

[59] UN HRC – UN Human Rights Council: Situation of women and girls in Afghanistan; Report of the Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights in Afghanistan and the Working Group on discrimination against women and girls [A/HRC/53/21], 15 June 2023, https://www.ecoi.net/de/dokument/2093577.html, pp. 17-18

[60] Freedom House: Freedom in the World 2022 – Afghanistan, 28 February 2022, https://www.ecoi.net/de/dokument/2068625.html, section G3

[61] RFE/RL - Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty: Taliban's Closure Of Women's Shelters Leaves Afghan Women Vulnerable To Abuse, 9 July 2025, https://www.ecoi.net/de/dokument/2127131.html

[62] GIWPS – Georgetown Institute for Women, Peace and Security: Women Peace and Security Index 2021/22, https://giwps.georgetown.edu/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/WPS-Index-2021.pdf, p. 62

[63] GIWPS – Georgetown Institute for Women, Peace and Security: Women Peace and Security Index 2021/22, https://giwps.georgetown.edu/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/WPS-Index-2021.pdf, p. 62

[64] GIWPS – Georgetown Institute for Women, Peace and Security: Women Peace and Security Index 2021/22, https://giwps.georgetown.edu/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/WPS-Index-2021.pdf, p. 62

[65] OCHA: Afghanistan: Humanitarian Update, January 2025, 7 April 2025

https://www.unocha.org/publications/report/afghanistan/afghanistan-humanitarian-update-january-2025

[66] The New York Times: Taliban Seize Women’s Ministry Building for Use by Religious Police, 17 September 2021, https://www.nytimes.com/2021/09/17/world/asia/taliban-women-ministry-religious-police.html

[67] UNAMA - UN Assistance Mission in Afghanistan: Report on the Implementation, Enforcement and Impact of the Law on the Propagation of Virtue and Prevention of Vice in Afghanistan, April 2025

https://www.ecoi.net/en/file/local/2123932/pvpv_report_final_10_aprill_2025.pdf. p. 2

[68] HRW - Human Rights Watch: Afghanistan: Relentless Repression 4 Years into Taliban Rule, 5 August 2025, https://www.ecoi.net/de/dokument/2128215.html

[69] CEDAW – UN Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination Against Women: Concluding observations on the fourth periodic report of Afghanistan [CEDAW/C/AFG/CO/4], 7 July 2025

[70] HRC - UN Human Rights Council (formerly UN Commission on Human Rights): Access to justice and protection for women and girls and the impact of multiple and intersecting forms of discrimination; Report of the Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights in Afghanistan, Richard Bennett [A/HRC/59/25], 16 June 2025, https://www.ecoi.net/en/file/local/2127745/g2508942.pdf (The situation of women and girls in Afghanistan), p. 2

[71] DFAT – Australian Government - Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade: DFAT Thematic Report on Political and Security Developments in Afghanistan (August 2021 to January 2022), 14 January 2022, https://www.ecoi.net/en/file/local/2067344/country-information-report-afghanistan.pdf , p. 15

[72] UN OCHA – UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs: Afghanistan Humanitarian Needs Overview 2022, 7 January 2022, https://www.ecoi.net/en/file/local/2066646/afghanistan-humanitarian-needs-overview-2022.pdf, p. 13

[73] UN OCHA – UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs: Afghanistan Humanitarian Needs Overview 2023 (January 2023), January 2023, https://reliefweb.int/attachments/2f525ec0-622e-47ee-bb0b-d411323dc054/AFG-HNO-2023-v06.pdf, p. 6

[74] WFP – World Food Programme: Afghanistan, Annual Country Report 2024, 27 March 2025, https://docs.wfp.org/api/documents/WFP-0000165338/download/?_ga=2.55441835.1470220911.1756280642-1266140242.1756117459, S. 3

[75] IPC – Integrated Food Security Phase Classification: Afghanistan: IPC Acute Food Insecurity Analysis – March-October 2025 (Issued 4 June 2025), 4 June 2025, https://reliefweb.int/report/afghanistan/afghanistan-ipc-acute-food-insecurity-analysis-march-october-2025-issued-4-june-2025 p. 1

[76] HRC – UN Human Rights Council (formerly UN Commission on Human Rights): The human rights situation in Afghanistan; Report of the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights [A/HRC/57/22], 4 February 2025, https://www.ecoi.net/en/file/local/2114653/g2416116.pdf, p. 4

[77] UN Security Council: Children and armed conflict in Afghanistan, Report of the Secretary-General, 21 November 2023, https://www.ecoi.net/en/file/local/2102858/N2336625.pdf, p. 10

[78] IOM – International Organisation for Migration: Baseline Mobility Assessment, June 2023, https://dtm.iom.int/sites/g/files/tmzbdl1461/files/reports/IOM-DTM-AFG_Baseline%20Mobility%20Assessment_Round%2016_1.pdf, p. 8

[79][79] IOM – International Organisation for Migration: Baseline Mobility Assessment, June 2023, https://dtm.iom.int/sites/g/files/tmzbdl1461/files/reports/IOM-DTM-AFG_Baseline%20Mobility%20Assessment_Round%2016_1.pdf, p. 10

[80] IOM – International Organisation for Migration: Displacement Tracking Matrix: Afghanistan Mobile Population Dashboard – District Level, ACVA R#2 (Mar. – Apr.) 2025, 2025, https://dtm.iom.int/online-interactive-resources/afghanistan-mobile-population-dashboard

[81] Researching Internal Displacement: Why Are IDPs in Kabul Reluctant to Return to their Places of

Origin following the Taliban's Takeover?, June 2024, https://researchinginternaldisplacement.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/Sayed_Afgh-Returns_270624.pdf, pp. 3-4

[82] UN OCHA – UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs: Afghanistan Humanitarian Needs Overview 2022, 7 January 2022, https://www.ecoi.net/en/file/local/2066646/afghanistan-humanitarian-needs-overview-2022.pdf, p. 14; see also UN OCHA – UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs: Afghanistan Humanitarian Needs Overview 2023 (available on reliefweb), https://reliefweb.int/attachments/2f525ec0-622e-47ee-bb0b-d411323dc054/AFG-HNO-2023-v06.pdf, p. 37-38

[83] UN Women – UN Entity for Gender Equality and the Empowerment of Women & UNHCR – UN High Commissioner for Refugees: Afghanistan Crisis Update; Women and Girls in Displacement, 1 March 2022, https://www.ecoi.net/en/file/local/2068691/Afghanistan_factsheet.pdf, p. 3

[84] Mediendienst Integration: Afghanen drittgrößte Flüchtlingsgruppe weltweit, 2 August 2023, https://mediendienst-integration.de/artikel/afghanen-drittgroesste-fluechtlingsgruppe-weltweit.html

[85] IOM – International Organisation for Migration: Displacement Tracking Matrix, Afghanistan, no date, https://dtm.iom.int/afghanistan

[86] Originally, the Pakistani government announced that holders of the Afghan Citizen Card (ACC) and the Proof of Registration Card (PoR) would be exempt. UNHCR – UN High Commissioner for Refugees: Emergency Update #9: Pakistan - Afghanistan Returns Response; As of 18 January 2024, 22 January 2024, https://data.unhcr.org/en/documents/download/106220, p. 1, footnote 1

[87] IOM – International Organisation for Migration: Flash Update – Sharp Rise in Forced Returns from Iran, 2 June 2025, https://afghanistan.iom.int/sites/g/files/tmzbdl1071/files/documents/2025-06/iom-afghanistanflash-update-1.pdf, p. 1

[88] IOM – International Organisation for Migration: IOM Warns of Mass Returns to Afghanistan, Urges Immediate Funding to Scale Up Response, 7 August 2025, https://www.iom.int/news/iom-warns-mass-returns-afghanistan-urges-immediate-funding-scale-response

[89] OHCHR – Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights: Afghanistan: Returns of Afghans creating multi-layered human rights crisis, 18 July 2025, https://www.ohchr.org/en/press-briefing-notes/2025/07/afghanistan-returns-afghans-creating-multi-layered-human-rights-crisis

[90] IOM – International Organisation for Migration: IOM warns of mass returns to Afghanistan, urges immediate funding to scale up response, 7 August 2025, https://www.iom.int/news/iom-warns-mass-returns-afghanistan-urges-immediate-funding-scale-response

[91] UN News: ‘The real challenge is still ahead’: UN warns on Afghan returnees, 8 August 2025, https://news.un.org/en/story/2025/08/1165610

[92] International Crisis Group: Who Will Run the Taliban Government?, 9 September 2021, https://www.ecoi.net/de/dokument/2059728.html

[93] HRW – Human Rights Watch: Afghanistan: Advancing Taliban Execute Detainees, 3 August 2021, https://www.ecoi.net/de/dokument/2057442.html; AIHRC – Afghanistan Independent Human Rights Commission: Violations of International Humanitarian Law in Spin Boldak District of Kandahar Province, 31 July 2021, https://www.aihrc.org.af/home/thematic-reports/91121

[94] UN General Assembly: The situation in Afghanistan and its implications for international peace and security; Report of the Secretary-General [A/76/328–S/2021/759], 2 September 2021, https://www.ecoi.net/en/file/local/2060189/sg_report_on_afghanistan_september_2021.pdf, pp. 5–6

[95] UN General Assembly: The situation in Afghanistan and its implications for international peace and security; Report of the Secretary-General [A/76/667–S/2022/64], 28 January 2022, https://www.ecoi.net/en/file/local/2067517/A_76_667--S_2022_64-EN.pdf , p. 5

[96] HRW – Human Rights Watch: “No Forgiveness for People Like You”; Executions and Enforced Disappearances in Afghanistan under the Taliban, November 2021,

https://www.ecoi.net/en/file/local/2064577/afghanistan1121_web.pdf (The Taliban's investigation into torture of former security personnel), pp. 1–2; see also: KP – Khaama Press News Agency: Taliban to investigate torture of former security personnel, 31 December 2021, https://www.khaama.com/taliban-to-investigate-torture-of-former-security-personnel-8687/

[97] AI – Amnesty International: Afghanistan: 13 Hazara killed by Taliban fighters in Daykundi province – new investigation, 5 October 2021, https://www.ecoi.net/de/dokument/2061295.html

[98] HRW – Human Rights Watch: “No Forgiveness for People Like You”; Executions and Enforced Disappearances in Afghanistan under the Taliban, November 2021, https://www.ecoi.net/en/file/local/2064577/afghanistan1121_web.pdf, pp. 1-2

[99] UN General Assembly: The situation in Afghanistan and its implications for international peace and security; Report of the Secretary-General [A/76/328–S/2021/759], 2 September 2021, https://www.ecoi.net/en/file/local/2060189/sg_report_on_afghanistan_september_2021.pdf, p. 5

[100] DRC – Danish Refugee Council: Afghanistan conference; The Human Rights Situation after August 2021, 30 December 2022, https://asyl.drc.ngo/media/13vhsflb/drc-afghanistan-conference-report-28nov2022.pdf, p. 19

[101] CRS – Congressional Research Service: Afghanistan: Post-Taliban Governance, Security, and U.S. Policy, 13 December 2017, https://www.fas.org/sgp/crs/row/RL30588.pdf, p. 16; BBC News: Afghanistan: Who's who in the Taliban leadership, 7 September 2021, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-58235639

[102] DRC – Danish Refugee Council: Afghanistan conference; The Human Rights Situation after August 2021, 30 December 2022, https://asyl.drc.ngo/media/13vhsflb/drc-afghanistan-conference-report-28nov2022.pdf, pp. 20-22

[103] UNICRI – United Nations Interregional Crime and Justice Research Institute: The Taliban in Afghanistan: Assessing New Threats to the Region and Beyond, 25 October 2022,

https://reliefweb.int/attachments/52bdb241-6635-484b-9010-aa4f6e960ce2/The%20Taliban%20in%20Afghanistan%20-%20Assessing%20New%20Threats%20to%20the%20Region%20and%20Beyond.pdf, S. 4

[104] UN Security Council: Fourteenth report of the Analytical Support and Sanctions Monitoring Team submitted pursuant to resolution 2665 (2022) concerning the Taliban and other associated individuals and entities constituting a threat to the peace stability and security of Afghanistan [S/2023/370], 1 June 2023, https://www.ecoi.net/en/file/local/2093255/N2312536.pdfp. 3

[105] UN Security Council: Thirteenth report of the Analytical Support and Sanctions Monitoring Team submitted pursuant to resolution 2611 (2021) concerning the Taliban and other associated individuals and entities constituting a threat to the peace, stability and security of Afghanistan [S/2022/419], 26 May 2022, https://www.ecoi.net/en/file/local/2073803/N2233377.pdf, p. 8

[106] UN Security Council: Fourteenth report of the Analytical Support and Sanctions Monitoring Team submitted pursuant to resolution 2665 (2022) concerning the Taliban and other associated individuals and entities constituting a threat to the peace, stability and security of Afghanistan [S/2023/370], 1 June 2023, https://www.ecoi.net/en/file/local/2093255/N2312536.pdf (The Taliban regime: Don't recognise it, resistance urges), p. 3

[107] BBC News: Afghanistan: Don't recognise Taliban regime, resistance urges, 8 September 2021, https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-asia-58484155?at_medium=RSS&at_campaign=KARANGA

[108] USDOS – US Department of State: Country Report on Terrorism 2021 - Chapter 5 - Haqqani Network (HQN), 27 February 2023, https://www.ecoi.net/de/dokument/2088213.html

[109] UN Security Council: Thirteenth report of the Analytical Support and Sanctions Monitoring Team submitted pursuant to resolution 2611 (2021) concerning the Taliban and other associated individuals and entities constituting a threat to the peace stability and security of Afghanistan [S/2022/419], 26 May 2022, https://www.ecoi.net/en/file/local/2073803/N2233377.pdf (The Taliban and other associated individuals and entities constituting a threat to the peace, stability and security of

[110] USDOS – US Department of State: Country Report on Terrorism 2021 - Chapter 5 - Haqqani Network (HQN), 27 February 2023, https://www.ecoi.net/de/dokument/2088213.html

[111] UN Security Council: Thirteenth report of the Analytical Support and Sanctions Monitoring Team submitted pursuant to resolution 2611 (2021) concerning the Taliban and other associated individuals and entities constituting a threat to the peace stability and security of Afghanistan [S/2022/419], 26 May 2022, https://www.ecoi.net/en/file/local/2073803/N2233377.pdf, p. 9

[112] USDOS – US Department of State: Country Report on Terrorism 2021 - Chapter 5 - Haqqani Network (HQN), 27 February 2023, https://www.ecoi.net/de/dokument/2088213.html; USDOS – US Department of State: Country Report on Terrorism 2022 - Chapter 5 - Haqqani Network, 30 November 2023, https://www.ecoi.net/de/dokument/2101658.html

[113] BBC News: Afghanistan: Don't recognise Taliban regime, resistance urges, 8 September 2021, https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-asia-58484155?at_medium=RSS&at_campaign=KARANGA

[114] UN Security Council: Thirteenth report of the Analytical Support and Sanctions Monitoring Team submitted pursuant to resolution 2611 (2021) concerning the Taliban and other associated individuals and entities constituting a threat to the peace stability and security of Afghanistan [S/2022/419], 26 May 2022, https://www.ecoi.net/en/file/local/2073803/N2233377.pdf, p. 10-11

[115] UN Security Council: Thirteenth report of the Analytical Support and Sanctions Monitoring Team submitted pursuant to resolution 2611 (2021) concerning the Taliban and other associated individuals and entities constituting a threat to the peace, stability and security of Afghanistan [S/2022/419], 26 May 2022, https://www.ecoi.net/en/file/local/2073803/N2233377.pdf (The Taliban and other associated individuals and entities constituting a threat to the peace, stability and security of

[116] UN Security Council: Thirty-second report of the Analytical Support and Sanctions Monitoring Team submitted pursuant to resolution 2610 (2021) concerning ISIL (Da’esh), Al-Qaida and associated individuals and entities [S/2023/549], 25 July 2023, https://www.ecoi.net/en/file/local/2095654/N2318974.pdf (The situation in the Middle East (including the Arab Republic of Syria and the State of Iraq)), p.

[117] UN Security Council: Thirty-fifth report of the Analytical Support and Sanctions Monitoring Team submitted pursuant to resolution 2734 (2024) concerning ISIL (Da’esh), Al-Qaida and associated individuals and entities [S/2025/71/Rev.1], 6 February 2025

[118] CRS – Congressional Research Service: Afghanistan: Post-Taliban Governance, Security, and U.S. Policy, 15 October 2015, https://www.fas.org/sgp/crs/row/RL30588.pdf, p. 20

[119] UN Security Council: Sixteenth report of the Secretary-General on the threat posed by ISIL (Da’esh) to international peace and security and the range of United Nations efforts in support of Member States in countering the threat [S/2023/76], 1 February 2023, https://www.ecoi.net/en/file/local/2087156/N2303122.pdf (The threat posed by ISIL (Daesh) to international peace and security and the range of United

[120] UN Security Council: Thirty-second report of the Analytical Support and Sanctions Monitoring Team submitted pursuant to resolution 2610 (2021) concerning ISIL (Da’esh), Al-Qaida and associated individuals and entities [S/2023/549], 25 July 2023, https://www.ecoi.net/en/file/local/2095654/N2318974.pdf (The Islamic State in Iraq and Syria), p. 16

[121] USDOS – US Department of State: Country Report on Terrorism 2022 - Chapter 5 - Islamic State’s Khorasan Province, 30 November 2023, https://www.ecoi.net/de/dokument/2101641.html

[122] UN Security Council: Thirty-second report of the Analytical Support and Sanctions Monitoring Team submitted pursuant to resolution 2610 (2021) concerning ISIL (Da’esh), Al-Qaida and associated individuals and entities [S/2023/549], 25 July 2023, https://www.ecoi.net/en/file/local/2095654/N2318974.pdf, p. 16

[123] HRW – Human Rights Watch: Afghanistan: Surge in Islamic State Attacks on Shia, 25 October 2021, https://www.ecoi.net/de/dokument/2062826.html

[124] UN Security Council: Thirty-fifth report of the Analytical Support and Sanctions Monitoring Team submitted pursuant to resolution 2734 (2024) concerning ISIL (Da’esh), Al-Qaida and associated individuals and entities [S/2025/71/Rev.1], 6 February 2025

https://www.ecoi.net/en/file/local/2122781/n2504159.pdf (The Taliban's Governance in Afghanistan), p. 16

[125] ISW – Institute for the Study of War: Taliban Governance in Afghanistan, March 2024

[126] CT – Critical Threats: Mapping Anti-Taliban Insurgencies in Afghanistan, 22 November 2022, https://www.criticalthreats.org/analysis/mapping-anti-taliban-insurgencies-in-afghanistan

[127] Reuters, No current talks with Taliban, Afghanistan's Massoud says, promising guerrilla warfare, 29 September 2023, https://www.reuters.com/world/asia-pacific/no-current-talks-with-taliban-afghanistans-massoud-says-promising-guerrilla-2023-09-29/