In ecoi.net’s English interface, the featured topics are presented in the form of direct quotations from documents. This may lead to non-English language content being quoted. German language translations/summaries of these quotations are available when you switch to ecoi.net’s German language interface.

Overview of security in Afghanistan

Recent security-related developments [as of 30 August 2021]:

Note: This section is updated on at least a weekly basis.

“A powerful bomb blast struck the perimeter of Kabul's Hamid Karzai International Airport on Thursday, as civilians continued to seek to escape on flights from Taliban-controlled Afghanistan. At least 95 people were killed and 150 others wounded. The Pentagon confirmed 13 US service personnel were among those killed. The bombing came hours after Western governments had warned their citizens to stay away from the airport, because of an imminent threat of an attack by IS-K, the Afghanistan branch of the Islamic State group.” (BBC, 28 August 2021)

“A US drone strike in the Afghan capital Kabul has prevented another deadly suicide attack at the airport, US military officials say. The strike targeted a vehicle carrying at least one person associated with the Afghan branch of the Islamic State group, US Central Command said.The US had warned of possible further attacks as evacuations wind down.[…] ‘We are confident we successfully hit the target,’ he said, adding: ‘Secondary explosions from the vehicle indicated the presence of a substantial amount of explosive material.’ He said later that Central Command were aware of reports of civilian casualties following the drone strike. ‘It is unclear what may have happened, and we are investigating further,’ he said, adding that Central Command would be ‘deeply saddened by any potential loss of innocent life’.” (BBC, 30 August 2021)

“Taliban forces have sealed off Kabul’s airport to most Afghans hoping for evacuation, as the United States and its allies wound down a chaotic airlift that will end their troops’ two decades in Afghanistan. Western leaders acknowledged that their withdrawal would mean leaving behind some of their citizens and many locals who helped them over the years, and they promised to try to continue working with the Taliban to allow local allies to leave after President Joe Biden’s Tuesday’s deadline to withdraw from the country.“ (Al Jazeera, 28 August 2021)

“Working women in Afghanistan must stay at home until proper systems are in place to ensure their safety, a Taliban spokesman has told reporters. ‘It's a very temporary procedure," spokesman Zabihullah Mujahid said.’” (BBC, 24 August 2021)

“Just over a week after the Afghan government’s collapse and the Taliban’s return to Kabul, there are more questions than answers about how the Taliban, back in de facto power in Afghanistan after twenty years, will rule the country.

So far, the policy announcements from Taliban spokesmen are crafted to be reassuring, though vague, declaring that there will be no revenge taking, saying girls and women will continue to be allowed education and employment (within unclear parameters), telling journalists that they can continue to report and calling for calm. At the same time, the limited anecdotal reporting of Taliban interactions with the population in areas newly under their control paints a mixed picture. There appear to be instances of reprisals and intimidation, especially directed at Afghans associated with the erstwhile government and its foreign supporters. Kabul, apart from the desperate scenes at the airport related to the rushed and unplanned evacuation, is reported by some to have been largely quiet in the initial days, though there are also reports of Taliban harassing some of those trying to reach the airport. Information from elsewhere in the country is sparse. The disparate and inconsistent signals do not yet form a clear pattern. Even if they did, it should not be assumed that the current Taliban approach will be long-lasting.” (ICG, 24 August 2021)

“Barnett R. Rubin is a former senior adviser to the Special Representative for Afghanistan and Pakistan at the State Department, and a nonresident fellow of the Center for International Cooperation of New York University and the Quincy Institute for Responsible Statecraft. […] Afghans are facing a humanitarian catastrophe of daunting proportions. The world must take action — sooner rather than later. After 20 years of botched policy, the United States has a particular obligation to mitigate the oncoming disaster. Let us hope it can find the will to do what it can.” (Washington Post, 24 August 2021)

Note: The following chapters are updated on a monthly basis.

1. Security in the country [as of 11 August 2021]

2021

“The United Nations recorded 7,138 security-related incidents between 13 November and 11 February, a 46.7 per cent increase compared with the same period in 2020 and contrasting with traditionally lower numbers during the winter season. Established trends of incident types remained unchanged, with armed clashes accounting for 63.6 per cent of all incidents. Anti-government elements initiated 85.7 per cent of all security-related incidents, including 92.1 per cent of armed clashes. The southern, followed by the eastern and northern regions, recorded the highest number of security incidents. Those regions collectively accounted for 68.9 per cent of all recorded incidents, with Helmand, Kandahar, Nangarhar and Balkh Provinces recording most incidents. […] No party to the conflict achieved significant territorial gains. The Taliban maintained pressure on key transportation axes and urban centres, including vulnerable provincial capitals such as in Farah, Kunduz, Helmand and Kandahar Provinces. The Afghan National Defence and Security Forces continued to conduct operations to secure key highways and reverse Taliban gains, particularly in the south following recent Taliban offensives on Lashkar Gah and Kandahar cities.” (UNGA, 12 March 2021, p. 5)[i]

“On 15 January, the United States announced that the number of its military forces in Afghanistan had been reduced to 2,500.” (UNGA, 12 March 2021, p. 3)

“In a statement, the Secretary-General of NATO, Jens Stoltenberg, announced that the Ministers of Defence had decided to defer a final decision on the future of the NATO presence in Afghanistan pending further consultations ahead of the deadline of 1 May 2021.” (UNGA, 12 March 2021, p. 4)

“On 14 April, United States President Joe Biden announced that ‘U.S. troops, as well as forces deployed by our NATO Allies and operational partners, will be out of Afghanistan before we mark the 20th anniversary of that heinous attack on September 11th.’ The announcement was not totally unexpected given that the US-Taleban deal signed in Doha, Qatar on 29 February 2020 required the withdrawal of all foreign forces by 1 May 2021. However, the announcement was a significant departure from what many had expected given that, up to then, the US had claimed the withdrawal would be a condition-based. It was commonly construed, based on the US-Taleban Doha deal, that the conditions allowing a full withdrawal of foreign forces would be a significant reduction in violence and at least the framework for a political settlement between the government and the Taleban. Biden, however, made it clear that this was not the case, saying, ‘American troops shouldn’t be used as a bargaining chip between warring parties in other countries.’ […] The Biden administration’s withdrawal announcement, while not unexpected, has set in train a series of responses, affecting the political and security landscape in Afghanistan. The decision to make the troop withdrawal total and unconditional coupled with the Taleban’s persistent refusal to engage with the Islamic Republic in serious negotiations aimed at a political settlement has created the perception that the Taleban will push for a military takeover of the country following the full withdrawal of foreign forces in September. […] Of particular note is that, for the first time in 20 years, powerbrokers are speaking publicly about mobilising armed men outside ANSF and government structures. While the presence of militias has been a local fact of life for many Afghans for years […], never have public pronouncements about the need to mobilise, nor the wish to establish autonomous spheres of influence been expressed so brazenly.” (AAN, 10 June 2021)[ii]

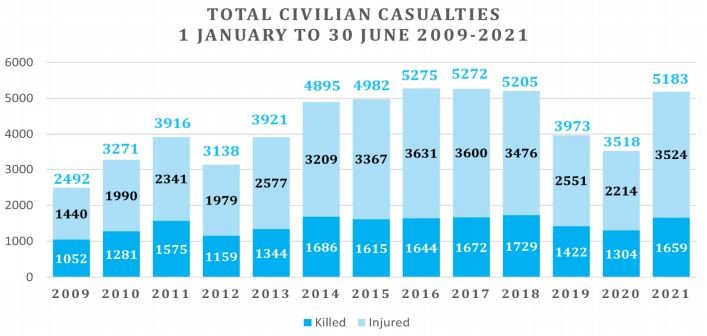

“Civilian casualties set to hit unprecedented highs in 2021 unless urgent action to stem violence” (UNAMA, 26 July 2021)[iii]

“Between 1 January and 30 June 2021, the United Nations Assistance Mission in Afghanistan (UNAMA) documented 5,183 civilian casualties (1,659 killed and 3,524 injured). The total number of civilians killed and injured increased by 47 per cent compared with the first half of 2020, reversing the trend of the past four years of decreasing civilian casualties in the first six months of the year, with civilian casualties rising again to the record levels seen in the first six months of 2014 to 2018. Civilian casualties increased for women, girls, boys, and men. Of particular concern, UNAMA documented record numbers of girls and women killed and injured, as well as record numbers of overall child casualties.” (UNAMA, July 2021, p. 1)

The UNAMA report on civilian casualties for the first six months of 2021 provides the following chart on civilian casualties:

“During the first six months of 2021, and in comparison with the same period last year, UNAMA documented a nearly threefold increase in civilian casualties resulting from the use of non-suicide improvised explosive devices (IEDs) by Anti-Government Elements. This was the most civilian casualties caused by non-suicide IEDs in the first six months of a year since UNAMA began systematic documentation of civilian casualties in Afghanistan in 2009. Civilian casualties from ground engagements, attributed mainly to the Taliban and Afghan national security forces, also increased significantly. Targeted Killings by Anti-Government Elements continued at similarly high levels. Airstrikes by Pro-Government Forces caused increased numbers of civilian casualties, mainly attributed to the Afghan Air Force.” (UNAMA, July 2021, p. 1)

“Anti-Government Elements were responsible for nearly 64 per cent of the total civilian casualties: 39 per cent by Taliban, nearly nine per cent by Islamic State Khorasan Province (ISIL-KP), and 16 per cent by undetermined Anti-Government Elements. Pro-Government Forces were responsible for 25 per cent of civilian casualties: 23 per cent by Afghan national security forces, and almost two per cent by pro-Government armed groups and undetermined Pro Government Forces. UNAMA attributed the remaining 11 per cent of civilian casualties to ‘crossfire’ during ground engagements, mainly between Afghan national security forces and Taliban, where the exact party responsible could not be determined (nine per cent) and ‘other’, mainly explosive remnants of war where the responsible party was unable to be determined (two percent). The number of civilian casualties attributed to Anti Government Elements increased by 63 per cent compared with the same period in 2020, while the number of civilian casualties attributed to Pro Government Forces increased by 30 per cent.” (UNAMA, July 2021, pp. 3-4)

“The escalation of war and violence in different parts of Afghanistan, especially in the last two months, has seriously damaged the lives of the Afghans in different areas. According to the findings of the Afghan Independent Human Rights Commission (AIHRC), civilian casualties, citizen displacement, and the harmful effects of violence in various provinces have increased as a result of conflict parties' failure to comply with international humanitarian law. Furthermore, according to the Commission, after taking districts, the Taliban impose restrictions on citizens' fundamental rights and freedoms in several provinces, particularly restricting women's access to basic rights and freedoms, such as access to health and education services.” (AIHRC, 17 July 2021)[iv]

For more information on the Taliban's treatment of civilians in areas under their control, see Section 2.2.

“UNICEF is shocked by the rapid escalation of grave violations against children in Afghanistan. In the last 72 hours, 20 children have been killed and 130 children have been injured in Kandahar province; 2 children were killed and 3 were injured in Khost province; and in Paktia province, 5 children were killed and 3 were injured. The atrocities grow higher by the day.” (UNICEF, 9 August 2021)[v]

“With the ongoing withdrawal of the United States’ military forces and the consequent weakening of the Afghan government, the Taliban now controls much of the territory of Afghanistan and most of its northern borders, posing a threat to its three immediate northern neighbors (Tajikistan, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan), other countries in the region (Kazakhstan and China), and even the Russian Federation. […] The situation remains fluid and unpredictable, not only because the fall of northern Afghanistan to the Taliban was so unexpected and quick but additionally because ethnic Tajiks, Turkmens and Uzbeks live on both sides of the border (Yandex Zen, May 11). For the last 20 years, Kabul-based journalist Fakhim Sabir points out, “the Afghan North was always the center of resistance to the Taliban.” Its peoples played a key role in overthrowing earlier Taliban rule, and Western forces have seldom fought there, battling in the south instead, the traditional base of the Taliban (Afganistan.ru, July 7).” (JF, 13 July 2021)[vi]

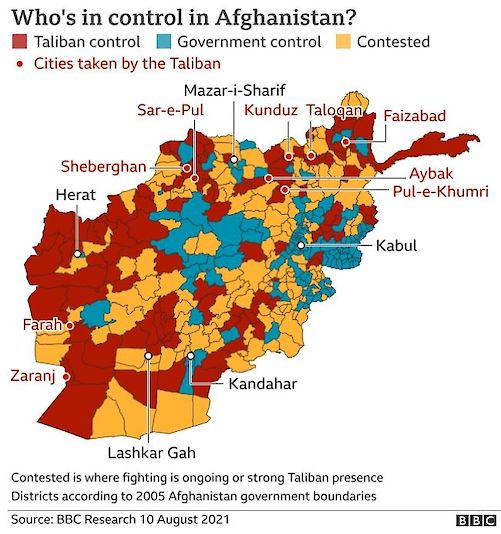

“The Afghan government has continued to lose district centres to the Taleban. By our reckoning, the insurgents have gained control of almost 200 district centres since 1 May, most of them since mid-June. Added to the ones they already controlled, that puts the insurgents in charge of just over half of all Afghanistan’s district centres. In a detailed new map published today, the Taleban’s apparent strategy becomes clearer: an initial push in the north, where resistance to their rule in the late 1990s/early 2000s was strongest, a focus on border crossings and other lucrative locations, and an avoidance so far of provincial capitals and of eastern areas which border Pakistan.” (AAN, 16 July 2021)

“It appears the Taliban have been emboldened in recent weeks by the withdrawal of US troops - retaking many districts from government forces and capturing a number of provincial capitals. The northern cities of Kunduz, Sar-e-Pul, Taloqan and Sheberghan fell to the Taliban in quick succession, as well as Zaranj in the south west. Research from the BBC Afghan service shows the militants now have a strong presence across the country, including in the north and north-east and central provinces like Ghazni and Maidan Wardak. They are also closing in on Herat in the west, and the southern cities of Kandahar and Lashkar Gah.“ (BBC, 9 August 2021)[vii]

“The Taliban has captured nine provincial capitals in Afghanistan in several days, including the cities of Sar-e-Pol, Sheberghan, Aybak, Kunduz, Taluqan, Pul-e-Khumri, Farah, Zaranj and most recently Faizabad.” (Al Jazeera, 10 August 2021)[viii]

The following map provided by BBC depicts the state of district control as of 10 August 2021. In this context, Taliban control means that "police headquarters and all other government institutions are controlled by the Taliban” (BBC, 9 August 2021):

As of 25 July 2021, UNOCHA reports 359 002 conflict induced internally displaced persons in Afghanistan. (UNOCHA, 5 August 2021, p. 1)[ix]

“Somewhere between 500 and 2,000 Afghan refugees are now estimated to be entering Turkey every day after undertaking the long and arduous journey from Afghanistan. The numbers are still lower than those recorded during a previous uptick in Afghans entering Turkey in 2018 and 2019, judging by apprehension statistics from the Turkish government, but they are expected to rise further.” (TNH, 3 August 2021)[x]

“At least 405 pro-government forces and 260 civilians were killed in Afghanistan in May, the highest total death toll in a single month since July 2019” (NYT, 1 June 2021)[xi]

“At least 703 Afghan security forces and 208 civilians were killed in Afghanistan in June, the highest count among security forces since The Times began tracking casualties in September 2018.” (NYT, 1 July 2021)

“At least 335 Afghan security forces and 189 civilians were killed in Afghanistan [July 2021].” (NYT, 5 August 2021)

[Note: The New York Times (NYT) figures are lower than UNAMA’s for methodological reasons. The cited NYT Afghan War Casualty Report includes all significant security incidents confirmed by New York Times reporters. Numbers are, according to the NYT, incomplete as many local officials do not confirm casualty information.]

For information on the security situation in Afghanistan during the period from January 2010 to September 2018, see the following report:

- ACCORD: Afghanistan: Entwicklung der wirtschaftlichen Situation, der Versorgungs- und Sicherheitslage in Herat, Mazar-e Sharif (Provinz Balkh) und Kabul 2010-2018, 7 December 2018

https://www.ecoi.net/en/document/2001546.html

2. State and Non-State Actors [as of 11 August 2021]

2.1. Afghan Government and Security Forces

“Three governmental entities share responsibility for law enforcement and maintenance of order in the country: the Ministry of Interior, the Ministry of Defense, and the National Directorate of Security. The Afghan National Police, under the Ministry of Interior, has primary responsibility for internal order and for the Afghan Local Police, a community-based self-defense force with no legal ability to arrest or independently investigate crimes. In June, President Ghani announced plans to subsume the Afghan Local Police into other branches of the security forces provided individuals can present a record free of allegations of corruption and human rights abuses. As of year’s end, the implementation of these plans was underway. The Major Crimes Task Force, also under the Ministry of Interior, investigates major crimes including government corruption, human trafficking, and criminal organizations. The Afghan National Army, under the Ministry of Defense, is responsible for external security, but its primary activity is fighting the insurgency internally. The National Directorate of Security functions as an intelligence agency and has responsibility for investigating criminal cases concerning national security. Some areas of the country were outside of government control, and antigovernment forces, including the Taliban, instituted their own justice and security systems. Civilian authorities generally maintained control over the security forces, although security forces occasionally acted independently. Members of the security forces committed numerous abuses.” (USDOS, 30 March 2021, executive summary)[xii]

“As of January 28, 2021, CSTC-A [Combined Security Transition Command-Afghanistan] reported 307,947 ANDSF [Afghan National Defence and Security Forces] personnel (186,859 MOD [Ministry of Defense] and 121,088 MOI Ministry of Interior]) biometrically enrolled and eligible for pay in APPS. There are an additional 7,715 civilians (3,031 MOD and 3,579 MOI).” (SIGAR, 30 April 2021, p. 66)[xiii]

„Funding for the Afghan Local Police (ALP), the largest and longest-lasting Afghan local defence force, ended on 30 September. Despite knowing this was going to happen for more than a year, it was only in early summer that the government decided what to do with the tens of thousands of ALP who are present in more than 150 districts and almost every province. The force has had a mixed record, with some units effectively and with determination defending their communities, while others have behaved so badly they have generated support for the Taleban. Yet whatever the record of individual units, dissolving the force is bound to have repercussions for security. […] The plan is for one third of ALP to be disarmed and retired, one third to be transferred to the Afghan National Police (ANP) and one third to the Afghan National Army Territorial Force (ANA-TF). The Ministries of Interior and Defence now have three months to sort, transfer and re-train, or disarm and retire about 18,000 armed men present in 31 of Afghanistan’s 34 provinces, in the middle of a war and a still-lingering pandemic.” (AAN, 6 October 2020)

“The Afghan National Army Territorial Force (ANA-TF) is the newest ANDSF force element. It is responsible for holding terrain in permissive (less violent) security environments. Falling directly under the command of regular ANA corps, the ANA-TF is designed to be a lightly armed local security force that is more accountable to the central government than local forces like the now-dissolved Afghan Local Police (ALP).” (SIGAR, 30 April 2021, p. 70)

“As a result [of the Taliban’s recent strategic gains], a worried government this week launched what it called National Mobilization, arming local volunteers. Observers say the move only resurrects militias that will be loyal to local commanders or powerful Kabul-allied warlords, who wrecked the Afghan capital during the inter-factional fighting of the 1990s and killed thousands of civilians.” (AP, 25 June 2021)[xiv]

The March 2018 German-language expert opinion on Afghanistan by Friederike Stahlmann provides further information on state actors in Afghanistan (Stahlmann, 28 March 2018, section 3.2)[xv]

2.2 Insurgent Groups

“[Anti-Government Elements] include members of the ‘Taliban’ as well as other non-State organized armed groups taking a direct part in hostilities against Pro-Government Forces including the Haqqani Network (which operates under Taliban leadership and largely follows Taliban policies and instructions), Al Qaeda, Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan, Islamic Jihad Union, Lashkari Tayyiba, Jaysh Muhammed, groups identifying themselves as Islamic State in Iraq and the Levant – Khorasan Province/‘Daesh’ and other militia and armed groups pursuing political, ideological or economic objectives including armed criminal groups directly engaged in hostile acts on behalf of other Anti-Government Elements.” (UNAMA, February 2021, p. 102)

“Terrorist and insurgent groups exploit Afghanistan’s ungoverned spaces, including the border region of Afghanistan and Pakistan. Islamic State’s Khorasan Province (ISIS-K), elements of al-Qa’ida, and terrorist groups targeting Pakistan, such as Tehrik-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP), continued to use the Afghanistan-Pakistan border region as a safe haven. The Government of National Unity (GNU) struggled to assert control over this remote terrain, where the population is largely detached from national institutions.” (USDOS, 1 November 2019)

Taliban

“The insurgency is still led primarily by the Taliban movement. The death in 2013 of its original leader, Mullah Umar, was revealed in a July 2015 Taliban announcement. In a disputed selection process, he was succeeded by Akhtar Mohammad Mansour, who in turn was killed by a U.S. unmanned aerial vehicle strike on May 21, 2016. Several days later, the Taliban confirmed his death and announced the selection of one of his deputies, Haibatullah Akhunzadeh, as the new Taliban leader. The group announced two deputies: Mullah Yaqub (son of Mullah Umar) and Sirajuddin Haqqani (operational commander of the Haqqani Network).” (CRS, 19 May 2017, p. 16)[xvi]

“The Taliban is an umbrella organization comprising loosely connected insurgent groups, including more or less autonomous groups with varying degrees of loyalty to the leadership and the idea of The Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan. The Taliban’s organisational structure is hierarchical, with an Amir ul – Muminin (Commander of the Faithful) on the top. He gives moral, religious and political statements, oversees judges, courts, and political commissions, assigns shadow governors and is in command of the military organization.” (Landinfo, 13 May 2016, p. 4)[xvii]

“By the start of the 2019 fighting season, which was announced on 12 April under the name ‘Al-Fath’ or ‘Victory’ the political backdrop had changed. In fact, extensive talks had already taken place in early 2019 between the Taliban and the United States of America. The first week of Al-Fath saw the highest level of security incidents in two years. The Taliban enjoy robust supplies of weapons, ammunition, funding and manpower, with 60,000 to 65,000 fighters and half that number or more of facilitators and other non – combatant members” (UN Security Council, 13 June 2019, p. 3)[xviii]

“[T]he Taliban had reportedly undertaken a restructuring and made numerous appointments to senior leadership positions inside Afghanistan, which were described as the removal of the older generation in favour of younger Taliban leaders. According to the same interlocutors, the provincial shadow and deputy shadow governors, along with the provincial military commanders, were all replaced in the Provinces of Bamyan, Baghlan, Kabul, Kapisa, Kunar, Laghman, Parwan, Samangan, Takhar and Uruzgan. Ousted individuals were reportedly removed owing to complaints from rank and file Taliban concerning deficiencies in logistical and financial support.” (UN Security Council, 30 May 2018, p. 5)

“Since the post-2014 U.S. military withdrawal from Afghanistan, there is little sign that the Taliban’s firepower has waned, or that the group is suffering from battle fatigue. Through persistent violence, the Taliban formations have proven they are still a major force in Afghanistan. It is likely the support structures the group has established over the last two decades remain intact. Since the fall of its so-called Islamic Emirate in 2001, the militant group has restricted the governments that followed from fully governing the country.” (JF, 2 June 2018)

“On 29 February, the Taliban and the U.S. signed an agreement that commits the U.S. to a fourteen-month phased withdrawal of military forces in exchange for Taliban commitments to prevent Afghanistan from being used as a safe harbour for terrorists. The agreement also obligates the Taliban to commence peace negotiations with the Afghan government and other Afghan power-brokers. This breakthrough comes after a decade of on-and-off U.S. and other efforts to catalyse a peace process, throughout which observers have questioned the Taliban’s willingness to negotiate a political settlement that will require substantive compromise. The group’s willingness to compromise remains an open question, but its interest in probing whether it could achieve its objectives through a negotiated settlement appears genuine – prompted, at least in part, by the elusiveness of a clear military victory.” (ICG, 30 March 2020) [xix]

“It [the 29 February 2020 agreement] committed the government in Kabul, which was not a party to the negotiations, to release up to 5,000 imprisoned Taliban members before peace talks commenced and the Taliban to release 1,000 prisoners in return. […] [T]he day after the agreement was signed, Afghanistan’s President Ashraf Ghani said his government could not honour terms it had not been present to negotiate.” (ICG, 11 August 2020, p.1)

“Negotiations for the US and Taliban had agreed that 5,000 Taliban prisoners would be released before they entered talks with the Afghan government. Thousands were freed - however, 400 remained in prison.” (BBC, 14 August 2020)

“The Afghan government said Monday it would not release the remaining 320 Taliban prisoners, stalling peace talks that are set to go ahead in a couple of days. […] Only last week, a traditional council reached an agreement to release a final 400 prisoners. Some of the prisoners set to be released have committed violent attacks on Afghans and foreigners.” (DW, 17 August 2020)[xx]

“The violence and mistrust that followed the U.S.-Taliban agreement amplified perceptions, voiced by some in Afghan civil society, media and government, that the Taliban might be prepared to engage in talks but not to compromise to forge a political settlement of the conflict. Indeed, the sequencing of peace efforts – beginning with bilateral commitments between the U.S. and Taliban, then moving to intra-Afghan talks that might end the war – allowed the insurgent movement to participate in the process without making significant concessions and with their leverage enhanced by those the U.S. made.” (ICG, 11 August 2020, p. 2)

“In the year following the US-Taliban peace deal of February 2020 - which was the culmination of a long spell of direct talks - the Taliban appeared to shift its tactics from complex attacks in cities and on military outposts to a wave of targeted assassinations that terrorised Afghan civilians.

The targets - journalists, judges, peace activists, women in positions of power - appeared to suggest that the Taliban had not changed their extremist ideology, only their strategy.[…]

Having outlasted a superpower through two decades of war, the Taliban began seizing vast swathes of territory, threatening to once again topple a government in Kabul in the wake of a foreign power withdrawing.

The group is thought to now be stronger in numbers than at any point since they were ousted in 2001 - with up to 85,000 full time fighters, according to recent Nato estimates. Their control of territory is harder to estimate, as districts swing back and forth between them and government forces, but recent estimates put it somewhere between a third and a fifth of the country.” (BBC, 3 July 2021)

In his March 2021 analysis, Thomas Ruttig discusses “the question of whether the Afghan Taliban have changed their repressive pre-fall 2001 positions, particularly on rights and freedoms even their wider ideology, and if so, how much and whether for good”. (Ruttig, March 2021)[xxi]

“Women banned from going outside alone. Girls barred from attending school. Unmarried women forced to marry fighters. This was life for many Afghans under the Taliban’s brutal regime in the 1990s when the fundamentalist Islamist group conquered much of Afghanistan. It is also the new harsh reality for the tens of thousands of Afghan women who live in areas recently captured by the Taliban, which has seized dozens of rural districts across the country since the start of the foreign military withdrawal on May 1. Residents of Afghanistan’s northeastern countryside – the focus of the Taliban’s blistering military offensive – say the militant group has reimposed many of the repressive laws and retrograde policies that defined its 1996-2001 rule. When it ruled Afghanistan, the Taliban forced women to cover themselves from head to toe, banned them from working outside the home, severely limited girls’ education, and required women to be accompanied by a male relative when they left their homes. Many of those policies have returned in areas now under Taliban control, say residents. That is despite repeated claims by the Taliban that it has changed and that it would not bring back its notorious strictures.” (RFE/RL, 14 July 2021)[xxii]

“Taliban forces advancing in Ghazni, Kandahar, and other Afghan provinces have summarily executed detained soldiers, police, and civilians with alleged ties to the Afghan government, Human Rights Watch said today. Residents from various provinces told Human Rights Watch that Taliban forces have in areas they enter, apparently identify residents who worked for the Afghan National Security Forces. They require former police and military personnel to register with them and provide a document purportedly guaranteeing their safety. However, the Taliban have later detained some of these people incommunicado and, in cases reported to Human Rights Watch, summarily executed them.” (HRW, 3 August 2021)[xxiii]

“Following the fall of the Spin Boldak district of Kandahar province to the Taliban and the publication of reports of the killing of civilians by the group, the Afghanistan Independent Human Rights Commission (AIHRC) despite serious challenges in the area investigated and documented the incident and, in order to obtain reliable and accurate information, while referring to reliable local sources, it also interviewed a number of victims' families and eyewitnesses. The evidence indicates that the Taliban, in violation of international humanitarian law, committed retaliatory killings of civilians and looted the property of several local residents, including the properties related to former and current government officials.” (AIHRC, 31 July 2021)

Haqqani Network

The “Haqqani Network,” founded by Jalaludin Haqqani, a mujahedin commander and U.S. ally during the U.S.-backed war against the Soviet occupation, is often cited by U.S. officials as a potent threat to U.S. and allied forces and interests, and a “critical enabler of Al Qaeda.” […] Some see the Haqqani Network as on the decline. The Haqqani Network had about 3,000 fighters and supporters at its zenith during 2004-2010, but it is believed to have far fewer currently. However, the network is still capable of carrying out operations, particularly in Kabul city. […] The group apparently has turned increasingly to kidnapping to perhaps earn funds and publicize its significance.” (CRS, 19 May 2017, p. 20)

“Strength: HQN [Haqqani Network] is believed to have several hundred core members, but it is estimated that the organization is able to draw upon a pool of upwards of 10,000 fighters. HQN is integrated into the larger Afghan Taliban and cooperates with other terrorist organizations operating in the region, including al-Qa’ida and Lashkar e-Tayyiba.

Location/Area of Operation: HQN is active along the Afghanistan-Pakistan border and across much of southeastern Afghanistan, particularly in Loya Paktia, and has repeatedly targeted Kabul in its attacks. The group’s leadership has historically maintained a power base around Pakistan’s tribal areas.

Funding and External Aid: In addition to the funding it receives as part of the broader Afghan Taliban, HQN receives much of its funds from donors in Pakistan and the Gulf, as well as through criminal activities such as kidnapping, extortion, smuggling, and other licit and illicit business ventures.” (USDOS, 19 September 2018)

Al Qaeda

“From 2001 until 2015, Al Qaeda was considered by U.S. officials to have only a minimal presence (fewer than 100) in Afghanistan itself, operating mostly as a facilitator for insurgent groups and mainly in the northeast. However, in late 2015 U.S. Special Operations forces and their ANDSF partners discovered and destroyed a large Al Qaeda training camp in Qandahar Province—a discovery that indicated that Al Qaeda had expanded its presence in Afghanistan. In April 2016, U.S. commanders publicly raised their estimates of Al Qaeda fighters in Afghanistan to 100-300, and said that relations between Al Qaeda and the Taliban are increasingly close. Afghan officials put the number of Al Qaeda fighters in Afghanistan at 300- 500.” (CRS, 19 May 2017, p. 17)

“Al Qaeda (AQ) is still assessed to have a presence in Afghanistan and its decades-long ties with the Taliban appear to have remained strong in recent years. In May 2021, U.N. sanctions monitors reported that Al Qaeda ‘has minimized over communications with Taliban leadership in an effort to ‘lay low’ and not jeopardize the Taliban’s diplomatic position.’ In October 2020, Afghan forces killed a high-ranking AQ operative in Afghanistan’s Ghazni province, where he reportedly was living and working with Taliban forces, further underscoring questions about AQ-Taliban links and Taliban intentions with regard to Al Qaeda. In general, U.S. government assessments indicate that the Taliban are not fulfilling their counterterrorism commitments concerning Al Qaeda. For example, in its report on the final quarter of 2020, the Office of the Inspector General for the Department of Defense relayed an assessment from the Defense Intelligence Agency (DIA) that the Taliban maintain ties to Al Qaeda and that some AQ members are ‘integrated into the Taliban’s forces and command structure.’ In a semiannual report released in April 2021, the Department of Defense stated, ‘The Taliban have maintained mutually beneficial relations with AQ-related organizations and are unlikely to take substantive action against these groups.’” (CRS, 11 June 2021, pp.1-2)

“The security situation in Afghanistan remains fragile, with uncertainty surrounding the peace process and a risk of further deterioration. As reported by the Monitoring Team in its twelfth report to the Security Council Committee established pursuant to resolution 1988 (2011) (see S/2021/486), Al-Qaida is present in at least 15 Afghan provinces, primarily in the eastern, southern and south-eastern regions. Its weekly Thabat newsletter reports on its operations inside Afghanistan. Al-Qaida in the Indian Subcontinent (AQIS) operates under Taliban protection from Kandahar, Helmand and Nimruz Provinces.” (UN Security Council, 21 July 2021, p. 14)

Islamic State – Khorasan Province

“An Islamic State affiliate—Islamic State-Khorasan Province (ISKP, often also referred to as Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant-Khorasan, ISIL-K), named after an area that once included parts of what is now Iran, Afghanistan, and Pakistan—has been active in Afghanistan since mid-2014.” (CRS, 19 May 2017, p. 20)

“IS formally launched its Afghanistan operations on January 10, 2015, when Pakistani and Afghan militants pledged their allegiance to its so-called caliphate in Syria and Iraq[…]. Since then, IS-Khorasan has proved itself to be one of group’s most brutal iterations, attacking soft targets, targeting Shia populations, killing Sufis and destroying shrines, as well as beheading its own dissidents, kidnapping their children and marrying off their widows. […]

IS-Khorasan chose to base itself in Afghanistan’s Nangarhar Province, a strategic location bordering Pakistan’s tribal areas. Its recruits came from both sides of the porous border and could easily escape a surgical strike or military operation by fleeing to either side of the Durand line. […]

From the very beginning, IS-Khorasan identified its targets—Shia communities, foreign troops, the security forces, the Afghan central government and the Taliban, who had not previously been challenged by an insurgent group. […]

“At present, ISIL strongholds in Afghanistan are in the eastern provinces of Nangarhar, Kunar, Nuristan and Laghman. The total strength of ISIL in Afghanistan is estimated at between 2,500 and 4,000 militants. ISIL is also reported to control some training camps in Afghanistan, and to have created a network of cells in various Afghan cities, including Kabul. The local ISIL leadership maintains close contacts with the group’s core in the Syrian Arab Republic and Iraq. Important personnel appointments are made through the central leadership, and the publication of propaganda videos is coordinated. Following the killing of ISIL leader Abu Sayed Bajauri on 14 July 2018, the leadership council of ISIL in Afghanistan appointed Mawlawi Ziya ul-Haq (aka Abu Omar Al-Khorasani) as the fourth ‘emir’ of the group since its establishment.” (UN Security Council, 1 February 2019, p. 7)

“Beyond the Taliban, a significant share of U.S. operations have been aimed at the local Islamic State affiliate, known as Islamic State-Khorasan Province (ISKP, also known as ISIS-K). Estimates of ISKP strength generally ranged from 2,000 to 4,000 fighters until ISKP “collapsed” in late 2019 due to offensives by U.S. and Afghan forces and, separately, the Taliban. ISKP and Taliban forces have sometimes fought over control of territory or because of political or other differences. A number of ISKP leaders have been killed in U.S. strikes since 2016, and Afghan forces arrested and captured two successive ISKP leaders in the spring of 2020. U.S. officials caution that ISKP remains a threat, pointing to several high profile attacks attributed to the group in 2020. The United Nations reports that casualties from ISKP attacks in 2020 decreased 45% from 2019. Some suggest that the Taliban’s participation in peace talks or a putative political settlement could prompt disaffected (or newly unemployed) fighters to join ISKP.” (CRS, 11 June 2021, pp.5-6)

“Despite territorial, leadership, manpower and financial losses during 2020 in Kunar and Nangarhar Provinces, Islamic State in Iraq and the Levant-Khorasan (ISIL-K) (QDe.161) has moved into other provinces, including Nuristan, Badghis, Sari Pul, Baghlan, Badakhshan, Kunduz and Kabul, where fighters have formed sleeper cells. The group has strengthened its positions in and around Kabul, where it conducts most of its attacks, targeting minorities, activists, government employees and personnel of the Afghan National Defence and Security Forces. […] In its efforts to resurge, ISIL-K has prioritized the recruitment and training of new supporters; its leaders also hope to attract intransigent Taliban and other militants who reject the Agreement for Bringing Peace to Afghanistan between the United States of America and the Taliban and to recruit fighters from the Syrian Arab Republic, Iraq and other conflict zones.” (UN Security Council, 21 July 2021, pp. 14-15)

The March 2018 German-language expert opinion on Afghanistan by Friederike Stahlmann provides further information on non-state actors in Afghanistan (Stahlmann, 28 March 2018, section 3.1)

3. Sources

(All links accessed 12 August 2021, except if otherwise noted)

- AAN – Afghanistan Analysts Network: Hit from Many Sides 1: Unpicking the recent victory against the ISKP in Nangrahar, 1 March 2020 (available at ecoi.net)

https://www.afghanistan-analysts.org/en/reports/war-and-peace/hit-from-many-sides-1-unpicking-the-recent-victory-against-the-iskp-in-nangrahar/ - AAN - Afghanistan Analysts Network: Disbanding the ALP: A dangerous final chapter for a force with a chequered history, 6 October 2020 (available at ecoi.net)

https://www.ecoi.net/de/dokument/2039860.html - AAN – Afghanistan Analysts Network: Preparing for a Post-Departure Afghanistan: Changing political dynamics in the wake of the US troop withdrawal announcement, 10 June 2021 (available at ecoi.net)

https://www.ecoi.net/en/document/2053156.html - AAN – Afghanistan Analysts Network: Menace, Negotiation, Attack: The Taleban take more District Centres across Afghanistan, 16 July 2021 (available at ecoi.net)

https://www.ecoi.net/en/document/2057178.html - ACCORD – Austrian Centre for Country of Origin and Asylum Research and Documentation: Afghanistan: Entwicklung der wirtschaftlichen Situation, der Versorgungs- und Sicherheitslage in Herat, Mazar-e Sharif (Provinz Balkh) und Kabul 2010-2018, 7 December 2018

https://www.ecoi.net/en/file/local/2001546/Afghanistan_Versorgungslage+und+Sicherheitslage_2010+bis+2018.pdf - AIHRC – Afghanistan Independent Human Rights Commission: Violations of International Humanitarian Law in Spin Boldak District of Kandahar Province, 31 July 2021

https://www.aihrc.org.af/home/thematic-reports/91121 - AIHRC – Afghanistan Independent Human Rights Commission: Escalation of Violent Confrontations and a Rise in Violations of Human Rights (From 1st to 15th of Saratan 1400/June 22 to July 6, 2021), 17 July 2021

https://www.aihrc.org.af/home/research_report/91112 - Al Jazeera: Infographic: Taliban captures nine Afghan provincial capitals, 10 August 2021

https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2021/8/10/infographic-taliban-captures-afghan-provincial-capitals - AP – Associated Press: Taliban gains drive Afghan government to recruit militias, 25 June 2021

https://apnews.com/article/joe-biden-taliban-business-race-and-ethnicity-99ce5fbb7b9a176b4662fbd04c7cb142 - BBC News: Taliban prisoner release: Afghan government begins setting free last 400, 14 August 2020

https://www.ecoi.net/de/dokument/2035906.html - BBC News: Afghanistan's Ghani says 45,000 security personnel killed since 2014, 25 January 2019

https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-asia-47005558 - BBC News: Who are the Taliban?, 3 July 2021

https://www.bbc.com/news/world-south-asia-11451718 - BBC News: Mapping the advance of the Taliban in Afghanistan, 9 August 2021

https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-57933979 - CRS - Congressional Research Service: Afghanistan: Post-Taliban Governance, Security, and U.S. Policy, 6 June 2016

https://www.fas.org/sgp/crs/row/RL30588.pdf - CRS - Congressional Research Service: Afghanistan: Post-Taliban Governance, Security, and U.S. Policy, 19 May 2017

https://fas.org/sgp/crs/row/RL30588.pdf - CRS – Congressional Research Service: Afghanistan: Background and U.S. Policy: In Brief, 11 June 2021

https://www.ecoi.net/en/document/2008094.html - DW – Deutsche Welle: Afghanistan halts Taliban prisoner release, stalls peace talks, 17 August 2020

https://www.dw.com/en/afghanistan-halts-taliban-prisoner-release-stalls-peace-talks/a-54602409 - HRW – Human Rights Watch: Afghanistan: Advancing Taliban Execute Detainees, 3 August 2021 (available at ecoi.net)

https://www.ecoi.net/en/document/2057442.html - ICG – International Crisis Group: Are the Taliban Serious about Peace Negotiations?, 30 March 2020

https://www.crisisgroup.org/asia/south-asia/afghanistan/are-taliban-serious-about-peace-negotiations - ICG – International Crisis Group: Taking Stock of the Taliban’s Perspectives on Peace, 11 August 2020 (available at ecoi.net)

https://www.ecoi.net/en/file/local/2036300/311-taking-stock-of-taliban-perspectives.pdf - JF - Jamestown Foundation: Wilayat Khorasan Stumbles in Afghanistan; Terrorism Monitor Volume: 15 Issue: 5, 3 March 2016 (available at ecoi.net)

https://www.ecoi.net/local_link/320838/446328_en.html - JF - Jamestown Foundation: Islamic State a Deadly Force in Kabul, Terrorism Monitor Volume: 16 Issue: 7, 6 April 2018 (available at ecoi.net)

https://www.ecoi.net/de/dokument/1428951.html - JF - Jamestown Foundation: Taliban Demonstrates Resilience With Afghan Spring Offensive; Terrorism Monitor Volume: 16 Issue: 11, 2 June 2018 (available at ecoi.net)

https://www.ecoi.net/en/document/1435560.html - JF - Jamestown Foundation: Islamic State Emboldened in Afghanistan; Terrorism Monitor Volume: 16 Issue: 12, 14 June 2018 (available at ecoi.net)

https://www.ecoi.net/en/document/1435576.html - JF - Jamestown Foundation: The Taliban Takes on Islamic State: Insurgents Vie for Control of Northern Afghanistan; Terrorism Monitor Volume: 16 Issue: 16 (Author: Rahmani, Waliullah), 10 August 2018 (available at ecoi.net)

https://www.ecoi.net/en/document/1440615.html - JF – Jamestown Foundation: Taliban Controls Afghanistan’s Northern Borders, Unsettling Countries Near and Far; Eurasia Daily Monitor Volume: 18 Issue: 111, 13 July 2021 (available at ecoi.net)

https://www.ecoi.net/en/document/2055914.html - Khaama Press: 1 killed, another wounded in a magnetic bomb explosion in Kabul city, 16 March 2019

https://www.khaama.com/1-killed-another-wounded-in-a-magnetic-bomb-explosion-in-kabul-city-03494/ - Landinfo - Norwegian Country of Origin Information Centre: Afghanistan: Taliban – organisasjon, kommunikasjon og sanksjoner (del I), 13 May 2016 (available at ecoi.net)

https://www.ecoi.net/file_upload/1788_1463253776_taliban.pdf - NYT – New York Times: Afghan War Casualty Report: January 2021, 21 January 2021

https://www.nytimes.com/2021/01/07/world/asia/afghan-war-casualties-january-2021.html - NYT - The New York Times: Afghan War Casualty Report: April 2021, 30 April 2021

https://www.nytimes.com/2021/04/08/world/asia/afghan-war-casualty-report-april-2021.html - NYT – New York Times: Afghan War Casualty Report: May 2021, 3 June 2021

https://www.nytimes.com/2021/05/06/world/asia/afghan-war-casualty-report-may-2021.html?action=click&module=RelatedLinks&pgtype=Article - NYT – New York Times: Afghan War Casualty Report: June 2021, 1 July 2021

https://www.nytimes.com/2021/06/03/world/asia/afghan-war-casualty-report-june-2021.html - NYT – New York Times: Afghan War Casualty Report: July 2021, 5 August 2021

https://www.nytimes.com/2021/06/03/world/asia/afghan-war-casualty-report-june-2021.html - RFE/RL – Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty: Return To The 'Dark Days': Taliban Reimposes Repressive Laws On Women In Newly Captured Areas In Afghanistan, 14 July 2021 (available at ecoi.net)

https://www.ecoi.net/en/document/2057958.html - SIGAR – Special Inspector General for Afghanistan Reconstruction, Quarterly Report to the United States Congress, 30 April 2021 (available at ecoi.net)

https://www.ecoi.net/en/file/local/2050829/2021-04-30qr.pdf - Stahlmann, Friederike: Gutachten Afghanistan, Geschäftszahl 7 K 1757/16.WI.A, 28 March 2018 (available at ecoi.net)

https://www.ecoi.net/en/document/1431611.html - TNH – The New Humanitarian (formerly IRIN News): The Afghan refugee crisis brewing on Turkey’s eastern border, 3 August 2021

https://www.thenewhumanitarian.org/news-feature/2021/8/4/the-afghan-refugee-crisis-brewing-on-turkeys-eastern-border - UNAMA – UN Assistance Mission in Afghanistan: Quarterly report on the Protection of Civilians from 1 January to 30 September 2019, 17 October 2019

https://www.ecoi.net/en/file/local/2019223/unama_protection_of_civilians_in_armed_conflict_-_3rd_quarter_update_2019.pdf - UNAMA – UN Assistance Mission in Afghanistan (Author), OHCHR – UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (Author): Afghanistan; Protection of Civilians in Armed Conflict; Annual Report 2020, February 2021 (available at ecoi.net)

https://www.ecoi.net/en/file/local/2046014/afghanistan_protection_of_civilians_report_2020.pdf - UNAMA – UN Assistance Mission in Afghanistan: Afghanistan; Protection of civilians in armed conflict; Midyear report: 1 January—30 June 2021, July 2021

https://www.ecoi.net/en/file/local/2056652/unama_poc_midyear_report_2021_26_july.pdf - UNAMA - UN Assistance Mission in Afghanistan: Civilian casualties set to hit unprecedented highs in 2021 unless urgent action stem violence, 26 July 2021 (available at ecoi.net)

https://unama.unmissions.org/civilian-casualties-set-hit-unprecedented-highs-2021-unless-urgent-action-stem-violence-%E2%80%93-un-report - UNGA - UN General Assembly: The situation in Afghanistan and its implications for international peace and security; Report of the Secretary-General [A/72/888–S/2018/539], 6 June 2018 (available at ecoi.net)

https://www.ecoi.net/en/file/local/1435757/1226_1529480518_n1816567.pdf - UNGA - UN General Assembly: The situation in Afghanistan and its implications for international peace and security; Report of the Secretary-General [A/75/811–S/2021/252], 12 March 2021 (available at ecoi.net)

https://www.ecoi.net/en/file/local/2048484/A_75_811_E.pdf - UNICEF – UN Children’s Fund: At least 27 children killed and 136 injured in past 72 hours as violence escalates in Afghanistan, 9 August 2021 (available at ecoi.net)https://www.ecoi.net/en/document/2057964.html

- UNOCHA – UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs: Afghanistan: Weekly Humanitarian Update (26 July – 1 August 2021) , 5 August 2021 (available at ecoi.net)

https://www.ecoi.net/en/file/local/2057755/afghanistan_humanitarian_weekly_3_aug.pdf - UN Security Council: Eighth report of the Secretary-General on the threat posed by ISIL (Da’esh) to international peace and security and the range of United Nations efforts in support of Member States in countering the threat [S/2019/103 - E - S/2019/103], 1 February 2019 (available at ecoi.net)

https://www.ecoi.net/en/file/local/2002892/S_2019_103_E.pdf - UN Security Council: Ninth report of the Analytical Support and Sanctions Monitoring Team submitted pursuant to resolution 2255 (2015) concerning the Taliban and other associated individuals and entities constituting a threat to the peace, stability and security of Afghanistan [S/2018/466], 30 May 2018 (available at ecoi.net)

https://www.ecoi.net/en/file/local/1435051/1226_1528897591_n1813039.pdf - UN Security Council: Letter dated 10 June 2019 from the Chair of the Security Council Committee established pursuant to resolution 1988 (2011) addressed to the President of the Security Council [S/2019/481], 13 June 2019 (available at ecoi.net)

https://www.ecoi.net/en/file/local/2010658/S_2019_481_E.pdf - UN Security Council: Twenty-eighth report of the Analytical Support and Sanctions Monitoring Team submitted pursuant to resolution 2368 (2017) concerning ISIL (Da’esh), Al-Qaida and associated individuals and entities [S/2021/655], 21 July 2021 (available at ecoi.net)

https://www.ecoi.net/en/file/local/2057424/S_2021_655_E.pdf - USDOS – US Department of State: Country Report on Terrorism 2017 - Chapter 5 - Haqqani Network, 19 September 2018 (available at ecoi.net)

https://www.ecoi.net/en/document/1445040.html - USDOS – US Department of State: Country Report on Human Rights Practices 2020 – Afghanistan, 30 March 2021 (available at ecoi.net)

https://www.ecoi.net/en/document/2048097.html

[i] The UN General Assembly (UNGA) is one of the six principal organs of the United Nations and the only one in which all member nations have equal representation.

[ii] The Afghanistan Analysts Network (AAN) is an independent non-profit policy research organisation with its main office in Kabul.

[iii] The UN Assistance Mission in Afghanistan (UNAMA) is a political UN mission established on 28 March 2002 by United Nations Security Council Resolution 1401.

[iv] The Afghanistan Independent Human Rights Commission (AIHRC) is a national human rights organisation in Afghanistan, dedicated to promoting, protecting and monitoring human rights and the investigation of human rights abuses.

[v] The United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) was created by the United Nations General Assembly after World War II with the aim of providing aid to children.

[vi] The Jamestown Foundation (JF) is a Washington, D.C.-based information platform providing media and monitoring reports aimed at informing and educating policy makers and the broader policy community about events and trends in societies that are strategically or tactically important to the United States and in which public access to such information is often restricted.

[vii] The British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) is a British public service broadcaster headquartered in London.

[viii] Al Jazeera is a Qatar-based TV news network.

[ix] The United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) is responsible for mobilizing and coordinating humanitarian actors to ensure a coherent response to emergencies advocating the rights of people in need, promoting preparedness and prevention as well as facilitating sustainable solutions.

[x] The New Humanitarian (TNH) is an institutionally- independent news agency focusing on crises and advocating for improving humanitarian response.

[xi] The New York Times (NYT) is a US Daily Newspaper based in New York City. The NYT publishes the Afghan War Casualty Report, which includes confirmed casualty figures of pro-government forces and civilians throughout Afghanistan on a weekly basis. The Afghan War Casualty Report only includes security incidents confirmed by New York Times reporters across Afghanistan. It is therefore necessarily incomplete, the NYT notes, as many local officials refuse to confirm casualty figures.

[xii] The US Department of State (USDOS) is the US federal executive department mainly responsible for international affairs and foreign policy issues.

[xiii] The Office of the Special Inspector General for Afghanistan Reconstruction (SIGAR) is a US government body that provides oversight on reconstruction efforts in Afghanistan.

[xiv] Associated Press (AP) is an international news and press agency based in New York City.

[xv] Friederike Stahlmann is a researcher at the Max Planck Institute for Social Anthropology (Germany) with a focus on Afghanistan.

[xvi] The US Congressional Research Service (CRS) is a public policy research arm of the US Congress.

[xvii] The Norwegian Country of Origin Information Center Landinfo is an independent body within the Norwegian immigration authorities that provides COI services to various actors within Norway’s immigration authorities.

[xviii] The United Nations Security Council (UNSC), one of the six main organs of the UN, is responsible for maintaining international peace and security. The UNSC regularly publishes reports about their international missions and worldwide developments concerning politics, security, human rights etc.

[xix] The International Crisis Group (ICG) is a Brussels-based transnational non-profit, non-governmental organization that carries out field research on violent conflict and advances policies to prevent, mitigate or resolve conflict.

[xx] Deutsche Welle (DW) is the German international broadcaster, an independent, international media company.

[xxi] Thomas Ruttig is an analyst for the Afghanistan Analyst Network (AAN), an independent non-profit policy research organization headquartered in Kabul which provides analyses on Afghanistan and its surrounding region.

[xxii] Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty (RFE/RL) is a broadcasting organisation funded by the U.S. Congress. It provides news to countries in Eastern Europe, Central Asia and the Middle East.

[xxiii] Human Rights Watch (HRW) is an international non-governmental organisation, headquartered in New York City, which seeks to protect human rights worldwide.

This featured topic was prepared after researching within time constraints. It is meant to offer an overview on an issue and is not, and does not urport to be, conclusive as to the merit of any particular claim to refugee status, asylum or other form of international protection. Chronologies are not intended to be exhaustive. Every quotation is referred to with a hyperlink to the respective document.