Voices from the Districts, the Violence Mapped (2): Assessing the conflict a month after the US-Taleban agreement

On 5 April 2020, the Taleban released a statement (original in English here) accusing the US of breaking the 29 February ‘Agreement for Bringing Peace to Afghanistan’. The statement said the agreement allowed the Taleban to:

… attack Kabul administration all military centres whether in rural areas or in urban areas but Islamic Emirate, neither has attacked their centres in major cities, nor had carried out operations at major military centres. Only checkposts in some rural areas where the people were scare of enemy attacks have been attacked that is very less as compared to last year.

The statement went on to claim that the US and Kabul government had violated the agreement by not yet releasing 5,000 Taleban prisoners, “[r]epeated attacks on Mujahideen centres that are not even on the battlefield,” raids by US and ‘internal forces’ on the general public, attacks on “ordinary mujahidin… even though there were no fighting in that area,” with violations in Helmand, Kandahar, Farah, Kunduz, Nangarhar, Paktia, Badakhshan, Balkh and elsewhere.” The Taleban promised to increase “the level of fighting” in response if the “breach continued.”

In response, US military spokesperson Colonel Sonny Leggett tweeted:

USFOR-A has upheld, and continues to uphold, the military terms of the U.S.-TB agreement; any assertion otherwise is baseless. USFOR-A has been clear- we will defend our ANDSF partners if attacked, in compliance with the agreement.

The [Taleban] must reduce violence. A reduction in violence is the will of the Afghan people & necessary to allow the political process to work toward a settlement suitable for all Afghans. We once again call on all parties to focus their efforts on the global pandemic of COVID-19.

Although this report does not deal with the prisoners issue, its importance should be flagged up, as it could affect the war, given the Taleban have threatened to increase attacks if their men are not released, as well as intra-Afghan talks, as the prisoner exchange was meant to build confidence ahead of talks.[1] On 7 April, the Taleban called off today’s meeting between the two technical teams tasked with organising the list of prisoners to be freed, saying the release had “been delayed under one pretext or another till now” and the meetings with the government team had been “fruitless.”

The text of the 29 February US-Taleban agreement, as we reported at the time, did not hold the Taleban to a promise not to attack Afghan forces or civilians. The movement only agreed not to threaten the “security of the US and its allies.” The term ‘allies’ might or might not be understood to include Afghans. On 4 March, Commander of US and NATO forces in Afghanistan General Austin Miller said the US had always been “very clear” with the Taleban “about our expectations—the violence must remain low.” That day, a US airstrike on 4 March targeted Taleban whom the US military spokesman said had been attacking an Afghan National Security Forces (ANSF) checkpoint in Nahr-e Seraj in Helmand (also known as Gereshk), while the previous day, the Taleban had attacked 43 checkposts in the province. The lack of outrage from the Taleban suggested that they had breached some sort of understanding.

Following the eight-day long reduction in violence (RiV), both the Afghan government and US military said they would take defensive action only, although Minister of Defence Asadullah Khaled warned on 8 March that this could change: “If the Taleban do not stop their attacks by the end of the week, our troops will target the enemy everywhere.” On 19 March, the Ministry of Defence changed its stance to one of ‘active defence’, in the face of Taleban attacks. This, it said, gave it “the right to attack the enemy where they are preparing to attack,” ie to make pre-emptive attacks. (The order is pinned onto the home page of the MoD’s website.) Examples of such attacks were two airstrikes reported on 7 April: the Ministry of Defence said that, based on intelligence that the Taleban were planning attacks, it had ordered two air strikes in Uruzgan province, one in Khas Uruzgan district and the other to protect the provincial capital, Tirinkot.

Even before the Taleban’s 5 April statement, AAN had been trying to assess how the conflict was shaping up since the end of the RiV. This is our second assessment. In the week after the RiV ended, we found the conflict to be patchy, with calm still reigning in some districts and the Taleban resuming attacks in others and with the US military and ANSF in defensive mode.

Methodology

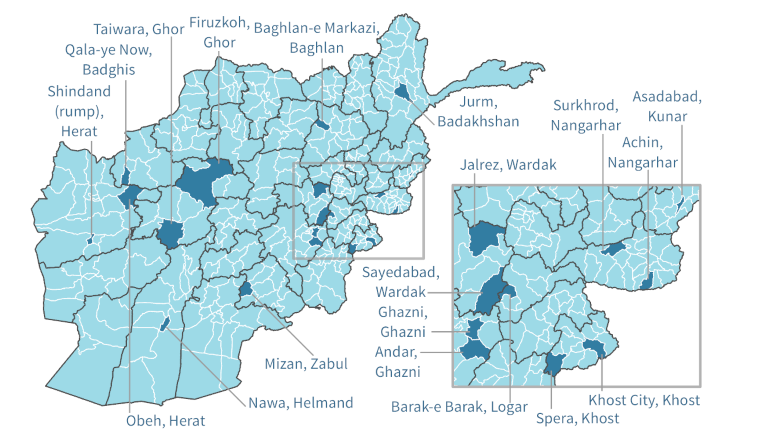

We have again used a mix of quantitative and qualitative data, with the aim of checking the perceptions, experiences and feelings of ordinary people against reported security incidents. We have drawn on the open-source Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED), which collects the dates, actors, locations, fatalities and modalities of all reported political violence and protest events across Afghanistan and other countries, for qualitative data.[2] Roger Helms has used ACLED’s data to produce visual illustrations of the violence. A graph shows the number of violent, security-related incidents per week, so far in 2020, compared to 2019. Two maps show the geographical spread of violent incidents in Afghanistan’s districts, and their number, both in absolute terms and per capita in the period 1 to 27 March.

Between 30 March and 4 April, we conducted interviews with 21 people in 12 provinces. Some were people we had earlier spoken to during the Reduction in Violence week and/or in the week after that ended. They are all ‘ordinary’ people, ie not security experts, government officials or combatants from either side. In order to ensure the readability of this report, we divided the interviews into six geographic areas: the southeast, central region, east, south, west and north. The questionnaire can be found in an annex to this report.

Analysis

Normally, in March and early April, the Taleban would be gearing up for their spring offensive. The conflict would be intensifying somewhat before, typically with some ‘spectaculars’ to mark the start of the offensive, large-scale, high-profile, coordinated attacks on district or provincial centres in different parts of the country, or a complex attack with mass casualties in the capital or another major population centre. In the last ten years, the Taleban have announced their spring offensive between 12 April and 12 May.[3] At this time of year, the weather is also a factor affecting when the conflict intensifies: prolonged winter weather, meaning snow still in the passes, can delay the onset of ‘normal’ fighting.

This year, as the graph above showing violent incidents for this year compared to last year shows, there was a significant fall in violent incidents during the RiV and a rebound afterwards. Since then, the violence has been less than usual, but significant, nonetheless and far more than during the RiV. However, within that general picture, there are significant patterns in different parts of the country as to how the conflict is developing this spring.

The Taleban have accused the US and government of launching “[r]epeated attacks on Mujahideen centres that are not even on the battlefield” and raids on the general public, but this is not bourn out by the interviews or the data. Interviewees in both Taleban-controlled and contested areas consistently describe the ANSF and the US military as having ceased operations, especially airstrikes and night raids. Some have reported the ANSF responding to Taleban attacks, including sometimes without taking due regard to civilians living nearby. As one interviewee in Zabul said: “As far as have seen, after the deal with the United States, the Taleban has been acting more aggressively and have conducted more attacks.” ACLED data for the 1-27 March also shows that, of the 599 entries, only 26 suggested aggression by government or US forces and of these, eight were against the Islamic State in Khorasan Province (ISKP or Daesh). The Ministry of Defence’s decision to launch pre-emptive strikes based on intelligence may change this picture somewhat.

The interviewees’ descriptions of conflict or lack of it pointed to an emerging distinction between districts controlled or largely controlled by the Taleban where civilians were still enjoying a reduction in violence because of the halt in government and US operations, and contested areas. There, civilians were seeing renewed violence, as the Taleban launched attacks, set IEDs, carried out targeted killings and set up checkposts. We tried to see if the data would support this apparent pattern, but without firm data on who controls which districts, it was not possible. It is also worth pointing out that in some places, where winter weather lingers, it is still unclear how the fighting season will unfold. The two maps show the geographic spread of the violence and intensity of the violence, both in absolute numbers and per capita, in the period 1-27 March.

The despair expressed by interviewees living in or near to contested areas in provinces such as Badakhshan, Badghis, Ghazni and Ghor was striking, as they described the renewed violence and lack of protection they felt from the government or, indeed, the reckless responses by government forces to Taleban attacks which increased the danger to civilian lives. Often, the evil of war was mentioned in the same breath as the coronavirus and quarrels in Kabul over who should lead the country. For example, a journalist from Badghis said:

Corona is one disaster and Taleban attacks another. It’s so worrying. Not only the Taleban, but also anyone else should have some humanitarian feeling and at least reduce the violence.

In the provincial capital of Ghor, a civil society activist after detailing the worsening security there, added:

There’s now corona and at the same time, those in the government are quarrelling in Kabul. There’s also the issue of peace with the Taleban and how it might go. The Americans have reached an agreement with the Taleban. If there’s no air support for government forces, their casualties will go up and more areas might fall to the Taleban. It’ll be catastrophic with people thinking about getting themselves out of those areas and migrating to live somewhere else. Our main concern is ending the war.

He was not the only interviewee to express doubts about the US-Taleban agreement. A human rights defender from Baghlan, for example, said: “The Taleban want to make peace with the US, but unfortunately they do not want to make peace with the people of Afghanistan.”

By contrast, many of the interviewees living in Taleban-controlled areas, who have seen a real reduction in violence this year because of the halt to airstrikes and night raids, supported the deal and hoped it would usher in better times. A journalist in Khost reported “People are happy with the deal, saying, ‘At least one part of the fighting is over now; the fighting between the ANSF and Taleban is not as it was in the past… [The people] want a permanent peace.’” In Logar, in Barak-e Barak district, an elder said:

[People] had been taking sleeping pills. They were afraid of the night raids by the government and the Taleban attacks during the day. People could not work on their farmlands. Since the RIV, the situation has changed and people are happy. They are busy with their own business.

In Nawa in Helmand, a farmer said he was very happy about the reduction in fighting:

In the past, people couldn’t farm their lands because there was always fighting, particularly, in the areas near any security checkpoints of the Afghan government forces. Right now, people are happily going to their land. And as I said, I went to Lashkargah the other day and there were no problems for us to travel and this makes us very happy.

Some of the interviewees, especially in the southeast, thought an appetite for peace among local Taleban was feeding into the reduced fighting there. In Zurmat, an elder said that the Taleban commanders, newly back from Pakistan “were sometimes sitting with the elders and were behaving well with the people. They are tired of war and want peace.” Another elder in Barak-e Barak in Logar said the RIV week had had a very positive impact on the situation:

Both people and Taleban have suffered [in the war]. The Taleban are also tired of war and they want peace. I have sat with the Taleban several times and they said they want to reduce the violence. They stressed ending the war.

Some of our interviewees believed there was a difference between war-weary local Taleban and the leadership. A humanitarian worker in Zabul, for example, who said many of his clients were Taleban or Taleban supporters, said:

The Taleban in the districts, the local Taleban are against the war and the violence. They are ordinary people guided and ruled through very a powerful leadership. Unless there is a clear order from the Taleban leadership, they cannot stop fighting. I have a feeling that the leadership does not want to make peace but wants to win this battle. Winning the war would mean a longer period of chaos, violence and war. The war is far from over in the districts.

Speaking to people around Afghanistan gives a snapshot of how the conflict is affecting different parts of the country.

People’s experiences around Afghanistan

The southeast

We interviewed two people in Khost and two in Paktia. All reported that there was still less violence than before. They thought this was partly due to the government and US’s defensive position, but also to local Taleban being less keen to fight.

In Khost, a journalist in Khost city and a civil society activist in Spera district, both reported that violence was less than is normal at this time of year. The journalist said there had been IEDs and magnetic bombs aimed at the police and some targeted killings, while the civil society activist described continuing attacks on the ANSF, but without casualties. He also said travel had become easier (although coronavirus was reducing this). He put the reduced violence down in his district to both more alert and better patrolling of the ANSF and pointed to IEDs defused and a car full of explosives intercepted and to local Taleban attitudes: “The RIV week was a good opportunity for the Taleban to understand that the war is not for the benefit of our country. The local Taleban say they are tired of the war and they hope peace comes so that they return to their ordinary lives.” The journalist pointed to the government and US’s defensive posture and, again, the local Taleban’s response:

In districts where the Taleban are in control, the US was conducting night raids against them, but now, due to the deal, there are no night raids. Therefore the Taleban have also reduced their violence. People are happy with the deal, saying at least one part of the fighting is over now; the fighting between the ANSF and Taleban is not as it was in the past… They want a permanent peace.

The principle of a school in Shwak district, Paktia, said violence in his district was somewhat reduced – he described two Taleban attacks on ANA convoys and some lacklustre shooting at security posts, but from far away, so without casualties. He thought the relatively low level of violence was due to the cold weather, with snow on the passes still preventing Taleban commanders returning from Pakistan, but also that “the Taleban are softer now compared to the past. They want peace, so they can start normal lives.”

In Zurmat district of Paktia, an elder said violence remained less than normal in what he called one of the most insecure districts in the country. He said the Taleban were still launching attacks on ANSF convoys, security posts and highway checkposts and firing rockets at the district centre, but it was less than before the RiV. The halt in US/government night raids and aircraft flying overhead meant people were sleeping better, he said. Days were also calmer, he said, because the Taleban had stopped disturbing people at home asking for food. “After they returned from Pakistan,” he said, “they do not ask people for food, but cook for themselves in the mosques.” He also said they had stopped questioning and ‘bothering’ people coming to Zurmat, he said, and, apart from government officials, people were now free to travel. The local Taleban commanders, he said, “were sometimes sitting with the elders and were behaving well with the people. They are tired of war and want peace.” He also thought, however, that “both sides, the Taleban and the government are waiting to see what happens” with the prisoner swap, and the Taleban commanders were “waiting to see what their leaders say.”

The centre

We interviewed three people in Maidan Wardak, two in Ghazni and one in Logar and heard mixed reports, of both continuing calm and renewed fighting.

From Barak-e Barak district in Logar, a tribal elder reported that violence was reduced, with only an attack on an ANA convoy and occasionally on security posts. Travel was easier, he said, and was not the only improvement people had seen.

They had been taking sleeping pills. They were afraid of the night raids by the government and the Taleban attacks during the day. People could not work on their farmlands. Since the RIV, the situation has changed and people are happy. They are busy with their own business.

The RIV week had a very positive impact on the situation, he said and both people and Taleban were tired of war. “I have sat with the Taleban several times and they said they want to reduce the violence. They stressed ending the war.”

A teacher in Andar district of Ghazni which, he said had a “very limited government presence,” reported there had been no night raids, airstrikes or Taleban attacks on government posts. People were happy and hoped, he said, it would lead to a permanent ceasefire in the country.

In a part of Ghazni city which neighbours Andar and is Taleban-controlled, a government employee described the conflict carrying on. Indeed, he said the only respite from war his neighbourhood had seen in the last four to five years was the 2018 three-day Eid ceasefire and the RiV in February. A Taleban attack on a government convoy heading south on 17 March, he said, had led to two days of fighting near the Shahbaz and Zelzela area and two tanks destroyed before the convoy returned to Ghazni city. After that, he said the ANA took up positions in five villages close to the border, Mushak, Niazi, Paya, Nughi, and Ashukwal and set up security posts (the Taleban had destroyed the security posts in these areas in 2018). The Taleban fired at the ANA in Nughi village, he said, and the ANA shelled back; one mortar landed on a civilian house killing two brothers.

The government official reported that the ANA had taken up temporary positions in homes in Ashukwal to watch the area and had destroyed their gates. He said that in the Shahbaz area, they also destroyed some empty shops, a petrol station and the walls of a vineyard and felled some trees. He described several other incidents (not all details given here) and said seven civilians had been killed in his area since the RiV was over.

Two residents of Jalrez district of Maidan Wardak reported that their district was calm. One said there had been just one recent incident, the kidnap and killing of a soldier from Daikundi travelling to Kabul. The other, a farmer, said his area was completely controlled by the Taleban and so, with no night raids or government attacks, it was “totally quiet and normal.” Locals, he said, were “happy and enjoying their lives.” He thought this was because the Taleban has promised to reduce violence when they signed their agreement with the US.

In Sayedabad district, also in Maidan Wardak, a resident reported the restart of fighting in Dara-ye Tangi and Sheikhabad: the Taleban had attacked an ANA base and police training camp in Dasht-e Top, he said, and the ANA had responded by shelling the Taleban who were in villages; one woman from Guli Khel was killed while getting water from the well, he said, while another woman from the same village was killed and her son and daughter injured, both in the previous week. He said the ANA had also retaliated with mortars when the Taleban attacked their camps in Sultankhel and the Durahi crossing. It was a difficult time, he said, for farmers trying to plough their land or prune their trees.

The east

We interviewed two people in Nangrahar and another in Kunar. Also reported that their areas were calm, but put this down entirely or mainly to the removal of ISKP.

In Asadabad in Kunar, a journalist reported that the situation there remained calm; key to this, she said was the surrender of Daesh fighters, rather than anything to do with the Taleban-US military/ANSF conflict. A university student in Surkhrod district of Nangrahar, also said her area had been relatively calm ever since ISKP bases were dismantled. The student, who is also a humanitarian volunteer, said she had travelled to a Taleban-controlled area of Sherzad District, something previously impossible. Her friends and relatives had also reported that freedom of movement between the districts had improved during and since the RiV. She thought the “quieter battlefield” might be a result of government forces not attacking the Taleban or possibly an indication of trust-building between government and Taleban.

A tribal elder in Achin district, Nangrahar said there had been no incident in his district, also since the fall of ISKP. Local people, through the Uprising Forces, which had a “member from each family” were taking care of security, he said. “People are tired of violence and war,” he said, “and do not allow anyone to fight in their area.” They were asking the government and the opposition to also say no to war. The people in Achin, he said, “are thirsty for peace.”

The south

Two people, one in Zabul and one in Helmand, have mixed experiences of the conflict since the RiV.

A humanitarian aid worker in Mizan district of Zabul who, in our last round of interviews said violence was worse than before the RiV, said the incidents and attacks by the Taleban on security posts and the targeted killings had continued. “The war is far from over in the districts” he said. “Since the deal with the United States, the Taleban have been acting more aggressively and have conducted more attacks.” Meanwhile, the ANSF was maintaining their “defensive stand.” He said most of his clients in the various districts were either Taleban or Taleban supporters, but said they were clearly against the war and the violence. He described them as “ordinary people guided and ruled by a very powerful leadership” and said that, “unless there is a clear order from the Taleban leadership, they cannot stop fighting.”

In a Taleban-controlled area of Nawa district of Helmand, a farmer and Taleban supporter said violence there was vastly reduced. “The Taleban are not fighting… Likewise, the foreign forces are also not carrying out any attacks or airstrikes in our area. No surveillance aircraft have been seen in our area.” Previously, he said, the Taleban were always fighting against the government and the local leadership “would always encourage fighters to carry out attacks on government posts in our area.” Right now, however, he said local leaders were putting no pressure on the fighters to “carry out attacks on this or that security post.” They were free, he said to fight or “just stay calm in their area of control.” People, he said, could get to their land, including in areas near government security posts and were happy.

The west

Of our interviewees, one in Badghis, two in Ghor and two in Herat, four reported that violence had intensified, with just a temporary respite in Shindand where flooding had halted the conflict, and people still waiting in Taiwara to see what would happen when the snow melted. All reported that the Taleban had launched attacks; in some places, the government had responded, in others not.

In Qala-ye Naw, provincial capital of Badghis, a journalist reported that since the RiV, the Taleban had intensified their attacks on government checkpoints in various districts, with casualties on “all sides.” He gave some examples: a Taleban attack in Muqur district on 30 March had left one member of the ANSF dead and two injured; an attack in Ab Kamari which had left several ANSF members had been killed and injured and “fighting on a daily basis” in Bala Murghab. Civilians living near checkpoints were at great risk, he said, and one woman had been killed in crossfire following a recent attack in Qadis district. “It’s only the Taleban that are attacking,” he said. “The government hasn’t launched any operations in Badghis.”

In the capital of Ghor province, Firuzkoh city, a civil society activist said security had got worse. “Fighting,” he said, “is restarting because the weather is getting warm and roads becoming open.” The Taleban had attacked government checkpoints on the Ghor-Herat road, he said, in Shahrak district and in areas neighbouring Herat’s Chesht-e Sharif district such as Dara-ye Takht, where they had set some communication towers on fire, creating problems for mobile phone users. In Shahrak, he said, the government air force had responded, inflicting casualties on the Taleban. He said fighting had also restarted in Dawlatyar district with Taleban and pro-government militias clashing. On 30 March, he said the Taleban has attacked a checkpoint near Firuzkoh city. All the attacks, he said, had been launched by the Taleban, with the government responding, and civilians being hurt in some. In the wake of the US-Taleban deal, he feared that if there was no US air support for government forces, their casualties would go up and more areas might fall to the Taleban.

In another district of Ghor, Taiwara, an estate agent told AAN that, although it was still cold, the snow had been thawing and it was becoming “more and more possible for fighting to restart.” He said there had been two security incidents in the last three weeks: an attack on a government checkpoint some two to three kilometres from the district centre and the detention of a young man, possibly because his brother is in the Afghan Local Police (ALP); elders and government officials were trying to secure his release. There is some discussion in the district government, he said, about retaliatory harassment of “ordinary family members of Taleban” coming to the clinic or bazaar or to get tazkeras (IDs): the government might want to do this, he said, to put more pressure on the Taleban not to harass ordinary people at least. In general though, he said, everyone was waiting:

We don’t know how this spring will be and whether it will differ from previous ones. For the moment, the Taleban are in their areas and positions and as the weather gets warmer, Talebs from southern provinces such as Farah, Kandahar and Helmand might join them. We don’t know if this will happen and, if it does, what they’ll do. There’s confusion and uncertainty about how this spring will go off.

The district of Obeh in Herat, is, as a government employee described it, entirely in Taleban hands except for the district centre. So far, he said, the government had not launched any operations against the Taleban, but the Taleban had attacked a government convoy going from Herat city to Chesht-e Sharif district through Pashtun Zarghun and Obeh districts. The convoy had responded and, he said, there had been casualties on both sides. Between Pashtun Zarghun and Obeh, he said the convoy had fired mortars on Taleban areas, injuring some civilians and damaging some civilian houses. Two members of the ANSF had also been killed in the district centre, in separate incidents.

Also, in Herat, a shopkeeper, in Shindand district, whom we spoke to after the RiV ended when he reported that fighting had resumed, with Taleban attacks and government responses, said the conflict had temporarily stopped. The reason was flooding caused by heavy rainfall, which had blocked main roads and destroyed some homes. However, he said:

If there’s going to be no peace between the government and the Taleban, the war will certainly restart here in Shindand. There’s a saying that when the wheat gets higher and trees get green, the war begins, because the Taleban will have some camouflage in the fields or among the trees and they will be able to strike and run. We’re worried about it. We hope the government and the Taleban sit down and arrive at some sort of peace.

The North

Two interviewees in the north, in Baghlan and Badakhshan both reported intensified attacks by the Taleban and the government under pressure.

A Human Rights defender in Baghlan-e Markazi of Baghlan province said the situation there was as violent as before the US-Taleban agreement was signed with Taleban “incursions” and attacks in Baghlan-e Markazi mainly directed at government forces. He listed some examples: the looting of a checkpost on Fabrika road; an attack on Naju post in which two security personnel were killed and six captured; attacks in Dand-e Shahabuddin in which a civilian was killed; an attack on ‘arbaki’ commander, Mullah Alam and; an attack on ‘local commander’ Mubarez in Sorkh Kotal. The Taleban also had checkpoints in the district and were “harassing people,” he said. The only positive change from before the RiV was an improvement in mobile coverage in the province.

A doctor in Jurm District, Badakhshan, said the Taleban had used the RiV to get ready for war and when the eight days were over, had carried out extensive attacks, capturing Yamgan district and parts of Jurm district. The security forces, he said, had suffered heavy casualties and some were taken hostage. The Taleban had also captured vehicles and heavy weapons which they were now using to attack the ANSF in Warduj and parts of Baharak district. He said IEDs, attacks on security posts and convoys had all increased in number. The government, he said, had taken no steps to try to capture Yamgan back: “If the government does not take any action, Warduj district will fall.”

Conclusion

So far, the only civilians to have benefited from the US-Taleban deal appear to be those living in Taleban-controlled areas where the defensive stance of the US and Afghan government forces has had a major and positive effect on their lives. Elsewhere, many civilians have seen the Taleban renewing their attacks. The movement’s 5 April statement suggesting their attacks on government checkposts were aimed at protecting local people who were “scare [sic] of enemy attacks” was not matched by our interviewees’ words. They spoke of fear and despair at the fresh violence.

The ANSF’s defensive posture should mean it is defending territory, but it has been under intense pressure in provinces such as Badakhshan and Badghis, as described by our interviewees. One wonders how ANSF morale has been affected by both the US-Taleban agreement and start of the staged withdrawal of US troops and the arguments in Kabul over who is leading the country.

At the moment, it seems that violence could be stepped up by both sides. The Taleban’s 5 April statement suggests they feel they have acted with restraint so far in not attacking the government in major cities and military centres, but that this could change. The government’s decision to start launching intelligence-based, pre-emptive strikes is certainly a response to continuing Taleban violence, but will also bring violence back into the lives of some of the civilians who have been enjoyed a measure of peace following the RiV.

At the heart of this is the contested reading of the US-Taleban agreement, whether it gives the Taleban free reign to attack the government and its forces, as they contend, or whether there was an understanding that violence would continue to be reduced. If the latter, then it would appear the Taleban have been testing the US, seeing what they can attack without suffering the consequences of, in particular, retaliatory airstrikes. An officer at Resolute Support told AAN on 2 April they were seeing signs of preparations for a spring offensive, including seeing Taleban “moving with impunity.” Before, he said, fighters had been moving in small groups, hiding their weapons. “Now they don’t care. They are moving in much larger groups displaying their weapons, including captured ANDSF weapons.” In previous years when the threat of airstrikes was reduced or eliminated, for example after the withdrawal of ISAF at the end of 2014 when President Obama’s orders were to attack ISKP only and not the Taleban, the mass movement of Taleban presaged fierce attacks on government-controlled centres. That Taleban are openly travelling is a worrying indicator, therefore, of possible intensifying conflict. What to do in the face of that is another matter.

Former US ambassador to Kabul Ron Neumann told AAN, “Fighting is a political action and so needs a military response which is also political.” In other words, any military response should support peace, however contradictory that might sound. The Taleban, he said, “needs to believe it does not have the choice of military victory. Thus, military action needs not only to save or support endangered Afghan forces, but also to convince the Taleban that further escalation is not in their interest.”

Underlying everything is the question of good intentions. This conclusion has focussed on the Taleban as they are the party to the conflict currently most engaged in it, but the same question could be asked of the Kabul administration: How much do they actually want to negotiate an end to the war and a permanent ceasefire. In this regard, interpreting the ‘real aims’ of the Taleban leadership goes on. What was the goal, for example of the talk given by Mullah Fazl Mazlum, former Guantanamo detainee, member of the Taleban negotiating team and “one of the most important and feared commanders of the Emirate and… head of the Army Corps in 2001” (biography here) to supporters in Pakistan at the end of March (reported here)? Fazl promised his audience they would have an amir, an emirate and sharia and could “grant them [some individuals from the current government] a ministry or some other post.” When Fazl said, “We will not let the sacrifices of our martyrs be wasted. God willing, we will see the victory,” was he rousing the troops for the war or, just possibly, using language supporters would understand, as he reassured them their demands could be met through negotiations?

Finally, worth noting is a theme introduced by several of the interviewees, in the southeast, Zabul and Logar, who thought the Taleban locally were receptive to a negotiated peace. However, they also questioned the intentions of the leadership and the capability and appetite of local Taleban to take independent action. In some areas, there may be potential for local peace-making. With Ramadan fast approaching, due around 23 April, during which fighting usually dampens down somewhat and religious ideals come to the forefront, peacemakers may find the ground more receptive for their message of ending the war. [4]Also, as the coronavirus spreads, the idea of fighting while compatriots are dying from disease may make those pursuing conflict look increasingly repugnant.

Edited by Thomas Ruttig

Annex: the Questionnaire

1. What has happened in your district/area since we last spoke/since the RiV ended?

2. If there has been violence, please tell us: Where, against whom, who launched the attack/s, were there any casualties?

3. If there has not been any violence or much less than normal: Why do you think there hasn’t been?

4. How is mobile phone coverage?

5. If travel had been difficult: Are people comfortable travelling now?

6. How do you feel about these changes (if the situation in your area has changed)?

[1] The US-Taleban agreement promised that up to 5,000 Taleban prisoners would be exchanged for up to 1,000 prisoners held by ‘the other side’. The Kabul government it seems had not agreed to this release – see a discussion of the politics and the legality of any release here. President Ghani had wanted staged releases in tandem with intra-Afghan talks and starting with the elderly, the sick, those nearing the ends of their sentences or accused of more minor offensives. The Taleban have been insisting on 5,000 men of their own choosing being freed.

[2] ACLED’s database covers both political violence and protests in Afghanistan spanning from January 2017 to the present, with data published weekly. ACLED researchers review approximately 60 sources in English and Dari/Farsi for reports of ‘political violence’ in Afghanistan. Approximately three-fifths of the ACLED data comes from the Afghan Ministry of Defence and the Taleban Voice of Jihad. ACLED tries to have each event geo-referenced and when that is not possible, to geo-reference the district and province instead. For steps taken to avoid artificially increasing the number of reported fatalities and to ensure that fatality estimates are as accurate possible, see ACLED’s Methodology and Coding Decisions, which can be found here.

[3] Taleban spring offensives were announced on: 12 April 2019, 25 April 2018, 28 April 2017, 12 April 2016, 25 April 2015, 12 May 2014, 27 April 2013, 15 April 2012, 1 May 2011

[4] The Afghanistan Independent Commission for Human Rights, for example, has been releasing a series of short videos calling for peace, ‘Put the Gun Down’. One features a man from Nangrahar saying his son and nephew have both been ‘martyred’ in the war, one fighting for the Taleban, the other with the ANA. He describes their graves, side-by-side, one with a white flag, the other a red, black and green flag. “Here we die,” he says. “There we die, it’s not the sons of the president, or the sons of ministers. It’s the poor people who are killed. That’s a disaster. No more war, please.”

Revisions:

This article was last updated on 9 Apr 2020